On 20 January the development aid sector suffered a huge blow: the Trump administration imposed a 90-day freeze on all US foreign development assistance. And the worst was yet to come, with secretary of state Marco Rubio announcing the dismantling of USAID in February, leading to the termination of thousands of aid delivery contracts.

US-based co-operative organisations active in development aid, such as NCBA-Clusa, Nreca International and the Overseas Cooperative Development Council (OCDC), were severely impacted by USAID’s shut down.

NCBA-Clusa, which has been involved in international co-operative development for over 65 years, with projects in nearly 100 countries, saw its annual revenue halved overnight.

“The sudden, unexpected termination of most of our foreign and domestic projects previously funded by the US government gutted our development work, cutting half our annual revenue… overnight,” it said in a statement.

The apex is now fundraising to continue operating internationally, while downsizing staff, closing offices and restructuring.

“This moment demands more than cuts, it calls for investment,” it added.

In May, the apex launched the NCBA Sustain and Grow Campaign to raise funding to sustain its core team and operations during this transition; pivot to a new, more resilient and diversified business model; and build a stronger, more innovative association that continues to develop, advance and protect co-operatives – at home, and around the world.

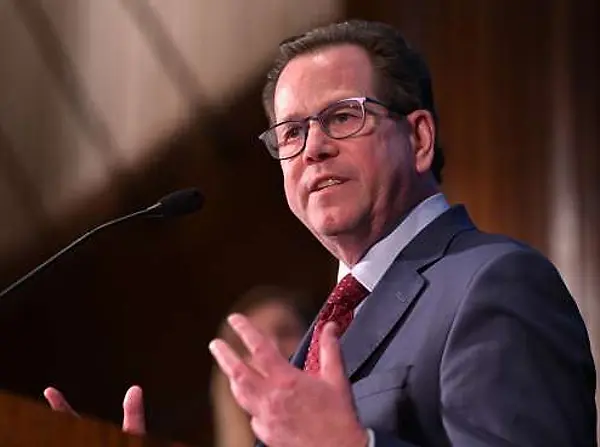

Casey Fannon, CEO and president of National Cooperative Bank (NCB), who spoke at the campaign’s launch, announced that NCB had given $500,000 to the campaign and urged other co-operatives to follow the bank’s lead. “I encourage all of you to support your association through the NCBA Sustain and Grow Campaign and, in doing so, help yourself and each other,” he said. “It’s through our collective voice that we can influence positive change and protect what we already have.”

Another organisation hit hard by the cuts is the OCDC, whose nine members include the World Council of Credit Unions (Woccu), Nreca International and NCBA Clusa, as well as other co-ops like Equal Exchange, Land O’Lakes and Health Partners.

“Each of these have lost the majority of their USAID funding,” says OCDC executive director Paul Hazen. “The US Department of Agriculture funding has also been cut. So we’ve all had to lay off staff, close offices. Here,at OCDC, I had to terminate all the staff, except for myself, as we try to regroup and figure out what the future is for us.”

All of OCDC’s research projects were shut down due to the funding loss. And while the organisation is looking for other donors, it has not yet received any funding.

Related: Calling all co-operators – new development fund needs you!

OCDC, along with the other co-ops affected, is continuing its advocacy work in Congress. “We’re hoping that Congress will restore funding for fiscal 2026 which will start on 1 October,” says Hazen, “and that legislation is working its way through Congress now. So we don’t know what will be restored, but we have some hope that some of the programmes will be restored.”

OCDC hopes it can secure funding to continue its previously USAID-funded co-op development programme, which was terminated when the funding stopped.

“It’s a very difficult situation,” warns Hazen. “Some of the co-op organisations will not survive. That’s clear. But we’re working to try to get funding reinstated, but then also, adjust to the new environment.”

Hazen adds that “most of the organisations do have some reserves that they’re able to access their own funding on an interim basis, but that’s not a long-term solution”. While he is hopeful that some level of funding will be restored next year, he fears that “it’s not going to be at the same levels as in the past”.

The focus will also have to shift to align with the administration’s priorities around national security and healthcare. Co-op development projects centred on climate or diversity and inclusion are less likely to receive funds.

The focus right now is to build the case for co-op development programmes within Congress.

“We’ve really marshalled our advocacy efforts with our co-op members across the country to contact their members of Congress to say how important these programmes are,” says Hazen, noting that solidarity is crucial during such challenging times for the sector.

“We’ve heard from people all over the world in support,” he adds. “We really appreciate that. From our perspective, we’re going to be rethinking how we approach co-operative development and it’s important that we have a global view. So the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) is an important platform for us to all come together. And because some of the other co-op development organisations in other countries have been affected, I think we’re going to have to join together and re-evaluate how we approach development and come up with some new approaches.”

Now, Hazen thinks, co-op development organisations will have to make an effective case for co-operatives to their respective governments, “reinforcing that when people have good jobs and good incomes, it helps national security”.

Related: African Union joins UN social and solidarity economy task force

“We know that from our experience,” he adds. “But I think we have to get the policy makers to understand that national security comes in more forms than just military might, that there’s economic security, and that comes along with developing economies, with co-operatives.”

For now, OCDC is staying flexible and adjusting as it goes along, and remains unable to make long-term plans.

USAID’s closure has already left a hole in many international aid organisations’ budgets, which has been widened by cuts in foreign aid made by other nations, including the UK, Germany, Canada, and France.

Sweden was another country to recently reduce its aid budget, from SEK 56bn to SEK 53bn for 2026. WeEffect, formerly known as the Swedish Cooperative Centre, is one of the country’s top recipients of foreign aid funding, which it channels across co-operative development projects in 20 states.

The cuts mean WeEffect will have to focus on 18 countries going forward, down from 20, and reduce its staff by 15%, says secretary general Anna Tibblin.

She acknowledges that “it’s been enormously challenging for all of the development organisations”, adding that WeEffect had feared all its funding being cut.

“Everybody’s received cuts, but we got the highest amount of funding,” she says. “So there’s a weird psychology, when you don’t know what to expect, because we’d also planned for zero, and then all of a sudden it goes better than expected, and you feel grateful because you receive budget cuts.

“We’re in a good place, in a really bad environment.”

One of WeEffect’s current projects is in the West Bank in Palestine, which will be able to grow as its funding continues.

While WeEffect was not receiving any direct funding from USAID, several of its partners were, which means it has been indirectly affected by its closure.

“We have to reprogramme the money that we have available to support our partners in the best possible way,” says Tibblin.

For example, in Moldova, where USAID was funding agricultural programmes, WeEffect worked with local farmer organisations to support their members. With all this funding disappearing, and the EU not compensating the loss, smallholder farmers are no longer given assistance from WeEffect with modern production techniques or market access.

This, she warns, leaves communities vulnerable to the influence of online trolls and populist messages.

“We don’t have that kind of large-scale funding to go in at bilateral level,” adds Tibblin, “but we see the effects on the ground. It affects the operations that we have because we can’t carry them out in the same way.”

“If the EU doesn’t manage to get support going into smallholder agriculture, it risks losing Moldova to Russia,” she says.

Similarly, in Zambia, a long drought has left 10 million people at risk of hunger,

“Our partner organisations who are trying to organise and mobilise people, continue to do that,” adds Tibblin, “but there aren’t any funds available to retract the development of a humanitarian crisis.”

Related: Can co-ops speed the pace towards sustainable development?

Like other co-operative development organisations, WeEffect is having to reconsider how it frames its work depending on the country it is operating in. In some contexts, the co-op development model can be described as more likely to tackle poverty and foster democracy. But human rights NGOs can be targeted by authoritarian governments, which can take measures to stop their work, such as imposing taxes or directly harassing them.

Furthermore, an increasingly conservative EU may not be as interested in a message around building democracy from below in countries like Zambia, but might be receptive to the idea of increasing market capacity and investment in the country, Tibblin explains.

“The shift in the whole donor landscape also affects what you want to fund.”

WeEffect was set up almost 70 years ago by Sweden’s co-operative movement, which continues to support its work. Its main focus is food security.

“They formed this organisation because they wanted to work together towards developing countries and organisation of people,” says Tibblin. “We support the organisations of smallholder farmers into co-operatives and to help create sustainable businesses, but that also ensures food security and contributes to local sustainable food security.

“If people have the means to develop local economies, feed their families, etc, it also hinders migration. It also hinders political instability. It also promotes local democracy. So the co-operative model fits everywhere. It’s always been relevant, but maybe it’s never been as easy to prove how relevant it is as now.”

In addition to the lack of funding, operating co-operative development projects in countries with different contexts comes with many challenges, from conflict to lack of democracy or lack of freedom to associate.

“Even co-operatives that are businesses not human rights organisations are increasingly questioned by their governments,” warns Tibblin. “So the freedom of organisation is an increasing challenge. The polarisation globally means it’s more difficult to get airtime to talk about why it is important to work together, why it is important to support people in developing countries, why it matters if we sit in England or Sweden or anywhere else, and just to talk about this.

“The whole world is connected but this is more difficult in these times of extreme polarisation.”

Another challenge is the need to raise awareness about the co-operative model.

“We support co-operatives, and co-operative-like organisations, and to us, it’s not so important what words we use. What we emphasise is that it’s member owned and democratic, or aspiring to be democratic, at least, and inclusive,” says Tibblin. “In some contexts, maybe we don’t even say ‘co-operatives’, because it has a very negative connotation from the past, then we’ll talk about startups, member owned businesses, or we’ll talk about the democratic private sector, or we’ll use other words. We try to work around it without getting stuck in the terminology. Because it’s not the terminology that is important, the work is.”

Throughout its many decades of activity WeEffect, which has a team of 150 staff around the world, has learnt a lot of lessons.

The first, says Tibblin, is that international co-op development is a way for co-ops to live their co-op values and principles. Another lesson is that getting different co-ops involved in supporting international co-op development projects can benefit both the development organisation and the co-ops funding it.

Related: Woccu says support for Ukrainian credit unions will continue

“Our board is not made up of development people,” she adds. “They’re leaders from the co-operative businesses in Sweden. So they’re not experts in development aid, but they are experts in banking, insurance and business and all of these enterprises, they benefit from working with WeEffect because they can take it back in their companies, among their employees, create engagement and show why their co-operative business is a different kind of business from the non co-operative business, because you have an international engagement, and it’s very concrete.

“We become a way to help our owners be values-driven for real. So it benefits their brand, it benefits their business, besides actually doing good in international co-operation.”

Bringing the expertise of leaders from different sectors has also helped WeEffect become more efficient, says Tibblin.

“The world is a challenging place and we don’t know what’s happening next,” she explains. “This is a time for co-operatives to shine, because it is in difficulties when the co-operative model is also at its best.

“It becomes the best version of itself. So I think our time is now. Academic research shows that in times of crisis, this economic model is more resilient. So let’s run with it. Be proud of it. Run with it. Develop it.”

An analysis by the Centre for Global Development suggests that Ukraine was the country which lost the most (US$1.4bn) from USAID’s closure. Other countries affected were Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Colombia, South Africa, Palestine, Bangladesh, Kenya, Afghanistan, and Tanzania, which all saw cuts of more than US$200m.

A more detailed picture of the impact the cuts to USAID funding have had on co-operatives and co-op organisations emerged after Politico magazine published a leaked list of awards to be terminated at USAID, which was allegedly sent to Congress.

According to this document, the current US administration terminated more than 5,300 grants and contracts managed by USAID and worth over $27bn.

These included awards to nine co-operatives organisations or organisations implementing co-operative projects.

These organisations ran 41 projects in 26 countries and, according to the document, suffered at a potential loss of $211,176,592.00 in funding, 27.96% of the total initially awarded.

USAID’s closure is having a domino effect on many other organisations outside the USA and their aid workers, some of whom have lost their jobs overnight. Yet, the biggest impact is on countries for which foreign aid is a lifeline, whose citizens are amongst the world’s most vulnerable.

Against this backdrop, can co-operatives worldwide step up efforts and boost funding to international co-operative development projects?