A much-loved wilderness centre in the Forest of Dean is now in co-op ownership. with ambitious plans to build a viable business offering a range of educational activities.

Community benefit society Wylderne has completed the purchase of the Wilderness Centre, which sits on 32 acres of grass meadows near Mitcheldean. The site includes five acres of old-growth woodland, and hosts a residential outdoors education and field studies centre, where thousands of local children have enjoyed their first formative nights away from home.

The site, which had been closed by Gloucestershire County Council in 2011 and reopened in 2014 after sale to a private owner, had been put back on the market, prompting locals to form Wylderne to save it for the community.

“We’re looking forward to welcoming back not only our local schools but for the first time everyone from the community who is interested in learning how to bring even more biodiversity to the forest and, in the process, benefit from contact with nature in this special place,” said Simon Dawson, a director of Wylderne. “Becoming a community hub is a great way to stimulate more co-operative ways of organising across the Forest of Dean.”

Aided by development agency Co-operative Futures, Wylderne has launched a community share offer to raise £150,000 to upgrade the site, with shares available for £50 each with the aim of keeping governance representative of the community. If people want to donate without becoming a member shareholder they are welcome to email [email protected]

“Just 20 minutes a day in green spaces, away from their screens can lift children’s mood and reduce stress and anxiety,” said director Paul Pivcevic. “It also boosts attention, memory, and overall cognitive development.”

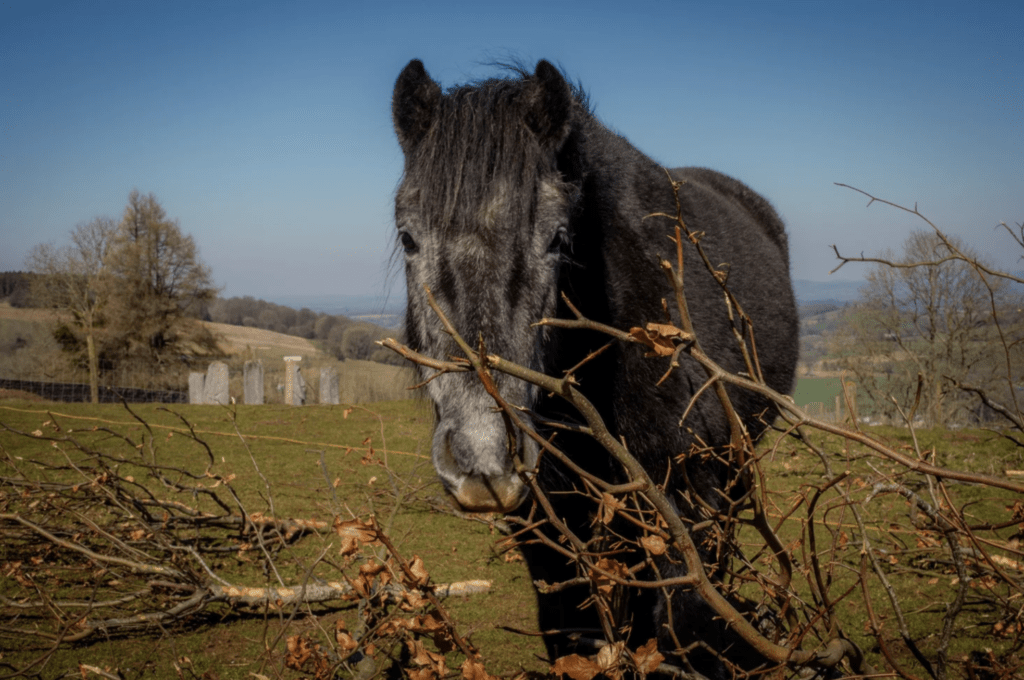

Plans include widening the range of groups using the centre, developing timber and forestry skills, and continuing to develop the rewilding programme started by two of Wyderne’s directors three years ago, which has brought conservation grazing cattle, Dartmoor ponies and wild boar onto the land. The co-op also hopes to provide outdoor study spaces for the forthcoming GCSE in natural history, alongside field studies facilities to students from Hartpury University.

Underpinning the project is a community ethos that shows how co-op ideas can actively reshape education, skills development and our relationship to the land. It also serves as an example of how the upcoming right to buy legislation can work effectively in a community.

“This place has for 50 years been a community asset,” says Dawson, “particularly when it was owned by the county council, and there was a lot of furore when they sold it in 2014.”

Related: Plunkett UK and Wates Developments launch community business plan

So when the centre went back on sale, the community benefit society (CBS) model seemed ideal; the site’s potential, Dawson feels, “needs to be realised by a community … I certainly I have my vision for the place – but that’s just my vision for the place.”

As well as bringing in a wider set of ideas, the CBS model is also useful in mobilising local skills. “The Forest of Dean has a very high level of volunteering compared to the rest of Gloucestershire,” says Dawson. “It has people who want to get involved. The forest has a strong culture of independent mindedness that goes back to the Middle Ages, having arguments with kings and land owners and so on.

“And people are quite skilled, the forest has a lot of micro businesses, and that made us think that the CBS model fitted the local culture of people wanting to get involved with an egalitarian approach.

“On the other side of that, the forest has young people with quite low levels of aspiration about what they could do and what the world holds for them. So we also wanted a vehicle where they can get involved and develop new skills. Those would be nature-based skills or land based skills – whether it’s working with wood or stone or in a natural environment.”

Wylderne’s education programme sees it work with schools and youth groups, often in innovative ways. “We’ve got a group of young Muslim men coming, and their thing is about how to be a British-born young Muslim man, and how to develop into that role. Then in a couple of weeks’ time, we’ve got young people coming who are refugees.

“It’s about personal growth – communication skills, team-working skills, resilience and so on, using nature as a vehicle for that. We’ll be talking to them about the natural environment and where they fit in with that.”

Related: OrganicLea food growing co-op offers family summer school

There is also community-based education, delivered in parallel with the district council, which is applying for the Forest of Dean to be a Unesco biosphere. “We have been invited to write the education piece for that application,” says Dawson. “That is environmental learning with community development going beyond the gates of the wilderness centre. Again, the co-op model fits with that. This is a community-focused, bottom-up, capacity-building endeavour, interlinked with environmental diversity, environmental health, nature connectedness, that feeds people’s sense of their belonging on this Earth and how to care for the Earth.”

Locals are glad to see the site returned to the community but, says Dawson, “we need to show how it can be a community asset … We’ve been doing a lot of communicating in different channels about our plans, but they’re just plans. I don’t know if it’s a British thing, but when it comes to our relationship with the land, there’s a lot of stuff around permission. People will say they’ve been driving past us for years, but they never explore, like it’s someone else’s place.

“We want people to say, I own part of this. One of the things we see when groups come here is, we’ve got a 30 acre estate but they don’t walk around it, they think you need permission.”

The society has devised a visual remedy for this, with a mural of the estate on the dining room wall. “We’re hoping that people, when they’re having breakfast, look at this mural of the estate, and they think, I haven’t been there. I haven’t been into that field, I haven’t gone to look at that tree. And it’s very clear, you can go anywhere you like.”

This feeds into the three aspects of development for the CBS, which Dawson defines as viability, vitality and the capacity to evolve. “Viability is obvious. We’ve got to make sure the income comes in. The vitality is really what I’ve just been talking about, which is bringing back that community engagement. The invitation is there, come up here and have a look around.

“And then the capacity to evolve is having mechanisms to listen to people’s ideas. We’ve got really interesting possibilities coming along.”

This includes potential partnerships to use more timber in local construction. “At the moment, most of the wood that’s commercially produced in the Forest of Dean actually goes for sawdust, so we’re looking at how we can educate builders and contractors about how they can use wood. That’s that’s not something we’ve ever done before, not something we know about, but we have a very convenient venue and educational facilities.”

This goes back to viability. “We’ve made a decision that while we do get funding, we are not going to rely solely on funding,” says Dawson. “We’re running as a business. That’s why we’re not a charitable CBS.”

Other projects include a land management plan for 25 acres of unimproved meadow, using conservation grazing with cattle, Dartmoor ponies and wild boar. Plans are also being made to manage five acres of ancient woodland.

“We want to use it as an educational vehicle, for people who may be interested in wilding and how you manage land these days on a regenerative basis. But also, there’s wider things about rewilding, which comes into eco literacy – about what does rewilding mean for us as humans? There’s lots of life lessons you can learn from from from wilding, things that you can reflect on and bring into your own life.

“The idea is our wild wildness will be both online and something that people experience here, and we’ll be updating that regularly. And the hope is that even if people aren’t coming here, they can check in to see what’s going on.”

Dawson hopes this will feed back into better management of the woods, which has “very badly handled” for the past 50 years. “We want to bring back coppicing and pollarding and so on. But tou have a wilding plan, and then nature decides how it’s actually going to happen.”

On a more practical level, the building – a Georgian manor house – needs a revamp, especially in terms of accessibility and retrofitting to keep it warm. The society also wants to increase capacity so it can host more than one group at a time. “It has a number of different spaces that have a different feel to them,” says Dawson. “There’s the manor house, there’s the glamping site with a marquee and a farm room. We need to develop that so that’s more of a viable option for people throughout the year.”