Henry Mintzberg’s tour story

Prof Henry Mintzberg is an Officer of the Order of Canada and Cleghorn professor of management studies at McGill University in Montreal. He is the author of 20 books on management as well as a book and a website on Rebalancing Society, his current focus.

Coop-Sapporo is not a traditional co-operative so much as an affiliation of social enterprises that it has organised to serve a range of community needs on the Japanese island of Hokkaido, from cradle to grave. This suggests a new model of the social economy: how communityship in the plural sector can play a consolidating role in rebalancing a society.

The invite

Some years ago, in search of an out-of-the-way place to visit in Japan, we went to the Oki Islands, the closest part of Japan to Korea. Hiroshi Abe – a local, and friend of a friend, who now publishes books and organises training programmes –welcomed us warmly and took us around. This past December, I heard from Abe-san again. He was writing on behalf of Coop-Sapporo, which delivers a host of services to the north island of Hokkaido, about the size of Ireland. They were celebrating their 60th anniversary, and were inviting me to do a keynote speech. I was told that its CEO and president, Hideaki Omi, was a particularly enthusiastic fan of my book, Rebalancing Society, and had all the managers of the co-op read it, in Japanese – reportedly several times.

Opportunity for Rebalancing Society

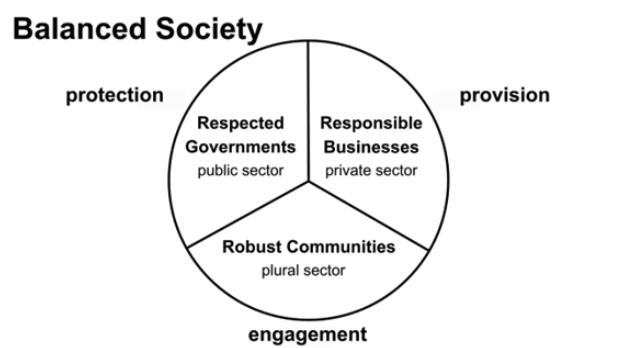

Since 1991, I have been working toward rebalance society (as the book in 2015, a website since 2021, and now a pamphlet in progress called For the Sake of Survival). Briefly summarised, this seeks to get us past two-sector pendulum politics – swinging between left and right, public and private sectors, with paralysis in the centre – to the idea of three-sector balance in society, across public sector governments that provide protections for the people, private sector businesses that supply many of their goods and services, and plural sector (civil society) associations that engage them in many of their community relationships.

Related: Japan’s legislators adopt resolution calling for promotion of co-ops

Co-operatives – essentially businesses, or social enterprises, operating in the plural sector, and owned by their members, not investors – are prime examples of the latter, alongside the many organisations that are owned by no-one (such as foundations and congregations, charities and NGOs).

Reading about this co-op, and in search of new models that could restore balance across the three sectors of society, particularly with regard to social enterprises, I suggested that we do a several-day tour of the island, to visit various facilities of the co-op, to become more fully briefed before the event.

En route in the bus

And so six of us spent the better part of a memorable week driving around Hokkaido in a big bus: Dulcie Naimer, my partner who has excellent insight about rebalancing society, Phil LeNir, an enthusiastic fan of these efforts who runs a company called CoachingOurselves.org, Hiro Abe, full of creative enthusiasm for the exercise, Masako Fujii, who proved to be much more than the translator for the trip, with her sophisticated knowledge of the subject matter and capacity to pull ideas together, and Emi Ogata, sent by the co-op to organise all this, who proved to be especially adept at re-organising it as well. We sat in the usual bus formation, until Dulcie wondered if we could turn the seats to face each other, since we were driving several hours every day. So we reconfigured the back of the bus into a workshop, as shown in the photograph, to discuss what we were finding as we rode along.

In advance, I had developed a list of about 40 questions to address about rebalancing society in general. Together, we reduced these to 10 that could be particularly relevant in our discussions, plus an 11th one that Phil had added in the previous week, about whether depopulation, which was a concern in all of Japan, but particularly Hokkaido, might be seen as an opportunity to rebalance society.

Guiding Questions for the bus

- How to get the message out about three-sector balance beyond two-sector politics?

- How to raise the profile of the plural sector, so that it can take its place alongside those called public and private?

- Also, how can we recover community in the face of individualising technologies?

- Why do some communities thrive and not others? Likewise with some social initiatives and social movements

- How to consolidate the many social initiatives into a global movement for reformation?

- How to get more robust and responsible organisations?

- How to activate the concerned but silent majority (people with mortgages, 30-70)? What inspires those people who are engaged for action?

- How to promote better in place of more (and replace GDP by DGB—Dynamic Global Balance)?

- Whatever happened to leadership? Where can we find the Nelson Mandelas now?

- What is dumbing us down? How to wake us up?

- Is “rebalancing society” the inevitable outcome of depopulation and degrowth in a capitalist society?

Depopulation as an opportunity

In fact, we were off to a good start, because of what happened at a couple of events in Tokyo during the previous week that shed light on Phil’s question. In a morning discussion with about 50 senior Japanese business executives, they raised the issue of stagnation in the Japanese economy, particularly with regard to depopulation. With Phil’s question in mind, I suggested they might see this as an opportunity rather than a problem, but I had no idea what that could be. The answer came that evening at a reception, when I met a Japanese professor of law who studies this very issue, Fusako Seki. When I posed Phil’s question, she answered, simply, yes, explaining that depopulation tends to bring out in their community people who have hitherto been isolated. She mentioned, in particular, the elderly, the handicapped, and women (presumably those secluded in their homes). We were to see this in action on our tour.

Kinds of co-ops

Some co-operatives are owned by their suppliers, as in farmer/agricultural ones, often to bypass costly middlemen in bringing their crops to market. Others are owned by their workers, as in the large Mondragon Federation in Spain, whose many businesses are each owned by their own workers, who are also own the overall federation – 70,000 of them. The most common are the co-ops owned by their customers, often supermarket chains and mutual insurance companies.

Related: Co-op councils tour Mondragon for lessons in economic revival

It’s been said about bacon and eggs that the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed. In customer co-ops, the members tend to be chickens, not pigs – they can join easily enough, and likewise leave – whereas in supplier and worker co-ops, the members tend to be pigs, with their livelihoods at stake. Coop-Sapporo is essentially a customer co-op, but being much more than that, as we shall discuss, both its members and the people of Hokkaido can be seen as committed pigs too.

Observing and reflecting

En route, we had an opportunity to visit a wide range of activities that come under the umbrella of Coop-Sapporo. On the first day, we visited a facility that bottles water, not only for the co-op supermarkets, but also to store large quantities for an expected earthquake. Next, we visited a plant that polishes and packages rice for the supermarkets and elsewhere, in partnership with a farmer co-op nearby, whose members grow the rice.

One day, we visited retail, in two very different ways – people coming to the co-op, and the co-op going to the people. We visited one of the 109 supermarkets, where members and other people of Hokkaido shop. (The co-op is also piloting a health-check service for their employees, with the intention of extending it to people in remote areas of the island.) Later, our bus followed one of the co-op’s 97 mobile grocery vans that go out to people in remote communities. It stopped in a tiny village, where its doors opened to become a small supermarket. We saw an elderly woman go up the stairs to buy her food, and then be walked home by a clerk who carried her bag.

Coop-Sapporo is particularly proud of the ATMs that it has installed in some of these vans, to give people access to banking services. Coop-Sapporo also has 1360 delivery vans that deliver grocery orders directly to peoples’ homes. These vans also recycle, by taking back used clothing.

On another day, we visited a school where Coop-Sapporo partners with the municipal government to provide lunches for the children, while “teaching health, manners, and community values.” Other visits included the co-op’s Eco-center that educates people about the problem of climate change, and a major logistics facility for the distribution of food. We were also shown “First Child Boxes,” given to members (to entice them to join). This indicates the co-op’s determination to provide cradle to grave services, starting with these baby boxes and ending with funeral halls.

In the midst of all this, as we drove between these visits, we were brainstorming in our bus about what we were seeing. Our ideas built, and began to consolidate – as did we, ourselves, as a little community – so that by the fifth day, we were ready to sit down in a room with a whiteboard to figure out what to make of all this. Over the course of about two hours, all of this came together, thanks to the use of an organigraph.

Picturing Coop-Sapporo as a model of social balance

The French word for organisation chart is organigram. Years ago, I started to draw organigraphs when I worked with a new organisation, to get past the narrow chart of who bosses whom. With a few of its people, we made a chart of how work flowed through the place. The diagram on the right shows how we started with the Coop-Sapporo organigraph.

The final organigraph shows Coop-Sapporo in the centre of a circle, with its members and other recipients of its services all around – cradle to grave, from baby boxes, to lunches for school children, through food, banking, and insurance services for adults, to funeral halls at the end of life – supplemented with other communal events (one of which, “Restaurant at a Farm,” is described at the end).

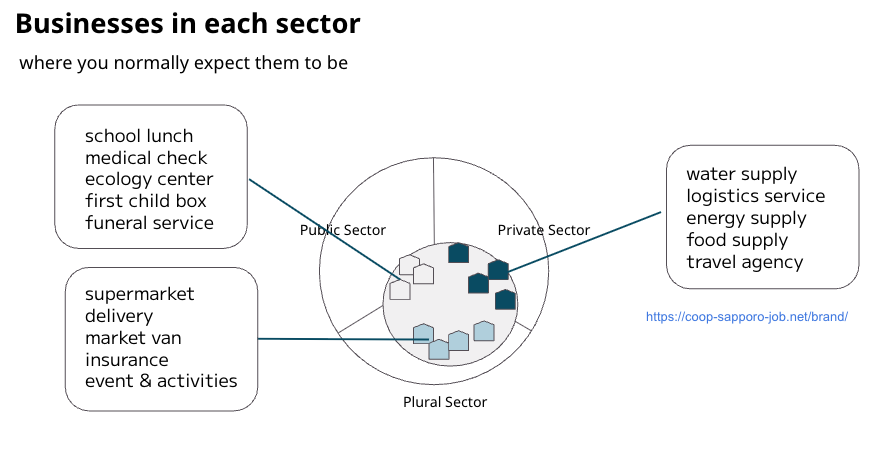

A breakthrough came when, looking at the organigraph, we concluded that Coop-Sapporo is not a just a co-operative, at least in the traditional sense of being in one business for its own members (as in mutual insurance companies), so much as an affiliation of social enterprises organised by a co-operative, some its own and some partnered with a government, as in the lunch program, with a business, as in water supply, even with another co-op, as in the rice operation. See the other circular diagram (right), that shows these businesses on the first diagram of the three sectors, some of them alone, within the plural sector, other times together with public, private, or plural sector partners. Coop-Sapporo can thus be seen as a fascinating new model of how communityship in the plural sector can play an integrative role in rebalancing society.

Coop-Sapporo’s businesses in each sector

Here are some other conclusions that we drew:

- Coop-Sapporo in a community (when delivering food to the people of Hokkaido).

- Coop-Sapporo as a community (with regard to its own members, 2 million strong, and employees – the latter having served over 14 years, on average – with Omi-san in the centre more than “on top”).

- Coop-Sapporo is a community, for economic and social development: it functions where self-interest meets common interest (with a motto of “One for all, all for one”).

- Coop-Sapporo is a collaborative structure, connected with all sorts of feedback loops.

- Coop-Sapporo represents a realignment of community, government, and business: it replaces or supplements the public sector when it cannot serve, and replaces the private sector where it chooses not to serve.

- Coop-Sapporo recycles, not only clothing, but also profits, into other activities that help to build the essence of communityship.

- Hence, Coop-Sapporo is an integrated model for social service/social enterprise rather than a decomposed model of market activities.

Keynote presenting and listening

The next morning, we presented our findings to about 50 of the co-op managers, beginning with a summary of rebalancing society as a concept, and then outlining our conclusions with the diagrams and the points above. The managers then formed into small groups, to discuss the following question – How can Coop-Sapporo take these ideas forward? – while the six of us, together with Omi-san, discussed “How can Coop-Sapporo become a model for the world?”

A debrief followed, during which the keynote listeners, who had been sitting with their back at each table, were now sitting in a circle in the middle to share what they heard, while Omi- san sat at the side, with his back to everyone else, himself now the keynote listener. Then he presented his own conclusions about what he heard this morning, with all the co-op managers listening.

Going forward

The next day, it was off to the local university to make the presentation for which I was originally invited, to celebrate Coop-Sapporo’s 60th anniversary. To put the icing on the cake, more than so to speak, this was followed by a remarkable lunch. Thirteen times a year, the co-op celebrates local ingredients with an event called “Restaurant at a Farm.” Beside a farm, tables and chairs are set up for about 40 diners – with the office staff of the co-op doing the serving. On this day, we were especially lucky. The chef was an award-wining one in Japan. Believe me, we ate brilliantly throughout this week, but never like this, never anywhere like this!

During the lunch, I presented Omi-san with a copy of my Rebalancing Society book, inscribed “To Omi-san, but for Akari”, his granddaughter, commenting that maybe one day, she will read it in English. Tears welled up in my new friend’s eyes.

Hokkaido co-op tour : a comment by Masako Fujii

Masako Fujii is an HR consultant and executive coach based in Kobe. A Fulbright scholar, majored in International Relations and Social Psychology, she served as HR director for European multinationals in Japan. She now facilitates leadership programmes to foster organisational health.

“There is no wealth but life – life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration.”

After returning to Kobe, I’ve been gradually remembering, absorbing, and making sense of everything I encountered during the Hokkaido Coop Tour. That’s when I came across this quote by John Ruskin. It perfectly captures what I felt through the interviews with Coop Sapporo employees. It turns out Mahatma Gandhi was also inspired by these words in shaping his idea of Sarvodaya. Coop Sapporo is rooted in something very profound and deeply human.

Depopulation

We talked and thought a lot about depopulation. In the town of Higashikawa, we came across the concept of teki-so (適疎), which roughly means “optimal sparsity.” The idea is to maintain a population size that fits the town’s sustainable economy, comfortable way of life, and natural landscape. I can still recall how soothing and peaceful it felt to drive through the rice fields and gardens – each one so thoughtfully cared for.

The term teki-so was coined by architect and city planner Yoshinobu Ashihara in his 1979 book The Aesthetic Townscape(『外部空間の構成』). It refers to the idea of “appropriately sparse spaces”—places that people find both comfortable and stimulating for urban activity.

Then, on the last day, during the D-HBR interview, Omi-san brought up the concept of Shuku-Ju(縮充) – translated by AI in Hiro’s summary as “shrinking with enrichment”. The term comes from a 2016 book by Ryo Yamazaki titled Shukujū in Japan (『縮充する日本』).

Yamazaki had already introduced a shift in perspective in his earlier 2012 book, The Age of Community Design (『コミュニティデザインの時代』). He suggested that Japan is returning to a more appropriate population size, recognising that the era of rapid economic growth was an exception in its long history, not the norm.

As a landscape architect, Yamazaki became increasingly focused on how people actually use spaces and how communities grow. His organisation, Studio-L (studio-l.org), has led an impressive series of projects that successfully foster people’s sense of connection and belonging. One such place is Ama-cho, where Hiro is located. This explains why Hiro happens to have his contact.

Yamazaki also explored the work of 19th-century English social thinkers, including John Ruskin and Robert Owen, in his 2016 book The Origins of Community Design (『コミュニティデザインの源流). And here, the threads start to connect, and we find that many of the original co-op pioneers in Rochdale were, in fact, Owenian in spirit.

Membership, community, and communityship

2025 marked the UN International Year of Cooperatives. There’s been active discussion within the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) about what a co-operative truly is, as they prepare to update the Coop Principles.

The current version, last revised in 1995, includes these seven principles: Voluntary and Open Membership; Democratic Member Control; Member Economic Participation; Autonomy and Independence; Education, Training and Information; Co-operation among Co-operatives; and Concern for Community.

Related: What did the International Year of Cooperatives achieve at global level?

That last principle especially points toward a spirit of openness. It recognises that the line between members and non-members isn’t rigid – and that co-operatives have a role in contributing to the sustainable development of their broader communities.

Here again, we’re reminded of how Coop Sapporo has been at the forefront of the international co-operative movement. Its thoughtful strategies and deeply engaged staff – how their faces lit up when they spoke about their mission! – are living expressions of the co-op principles.

Interestingly, none of the principles explicitly mention the “cycling of profits,” yet this is a key innovation that makes Coop Sapporo so effective in serving its community. It’s also what enables them to collaborate flexibly with both the public and private sectors.

Yamazaki mentioned in his book that there are two types of communities, geographical and thematic. It means there are communities in towns and there are communities online. Sometimes, as a hybrid, people get connected online and join real-world activities, like beach cleanups or hikes with small kids. Whatever the type is, I think when a community lacks communityship, the drive to share values and benefits with everyone, it becomes just a

closed group.

As Yamazaki has been activating and engaging different groups of people in different parts of Japan, perhaps it’s more fitting to call Yamazaki a communityship practitioner rather than a community designer. In Coop Sapporo communityship is the internalised norm among its employees, as we saw. This should be a place where “Communityship leads”. While the leader’s charisma is a strength, it also brings concerns – like how succession will be handled or how some workplace issues are addressed, I am sure they will find a way to keep on thriving in the manager-out fashion.

Now I’m beginning to think a community can be only for members, while communityship is for everyone. Probably communityship in an organisation thrives where people hold a broader perspective beyond their organisational boundaries.

It doesn’t arise from a sense of obligation to follow some ethical guidelines. Instead, it comes from within each of us, social human beings, who like to talk to people, work with people, and trust each other. It emerges from our natural willingness. I learned this with a real sense of conviction! I am deeply grateful.

Our choice

On the road, Phil and I talked about how easily humans are swayed by anxiety and a sense of superiority. That reminded me of a Native American folktale – The Story of Two Wolves. It tells of a battle inside each of us between a good wolf and an evil one. The outcome depends on which wolf we choose to feed. I guess when we feed the wrong one, we chase “more and more.” When we feed the right one, we aim for “better and better.”

One of the questions we asked in Hokkaido was: “How to balance common cause with self-interest?” Maybe one answer is just that: we make a choice. I would choose to feed the wolf “full of joy, peace, love, humility, kindness, and faith,” and let the one “full of anger, sorrow, regret, greed, self-pity, and false pride” go hungry.