The co-operative movement usually traces its origins to attempts to remedy problems and faults in the private (investor-controlled) economy. To replace narrow profit-driven enterprises with a more ethical, co-operative, community and democratic alternative.

As is well known, the initial focus of the Rochdale Pioneers was on replacing rapacious food retailers with co-operative suppliers of decent fare at affordable prices to ordinary working people through democratically run enterprises.

Two books by the same author – published just over a decade apart (2010-2022) – pose an interesting challenge. Is it time for co-operative development to shift focus from just the private sector to a greater interest in the public too – from the market to the state?

The author in question is John Restakis (pictured), a Greek-Canadian co-operative activist who has played a variety of roles in educational, community and co-operative development and education. The books I’m referring to are: Humanizing the Economy – cooperatives in the age of capita (2010), and Civilizing the State, with the sub-title Reclaiming Politics for the Common Good (2022).

While neither is exclusively about one sector of the economy – private, public sector or social (and co-operative) – their different focus is clear from the titles. The first represents the past, and to a large degree the present, of much of the international co-operative movement. Co-operatives have traditionally focused on humanising the private sector economy.

The second book focuses on the problems of the public sector as it grew and transformed into varieties of welfare states in the second half of the 20th century.

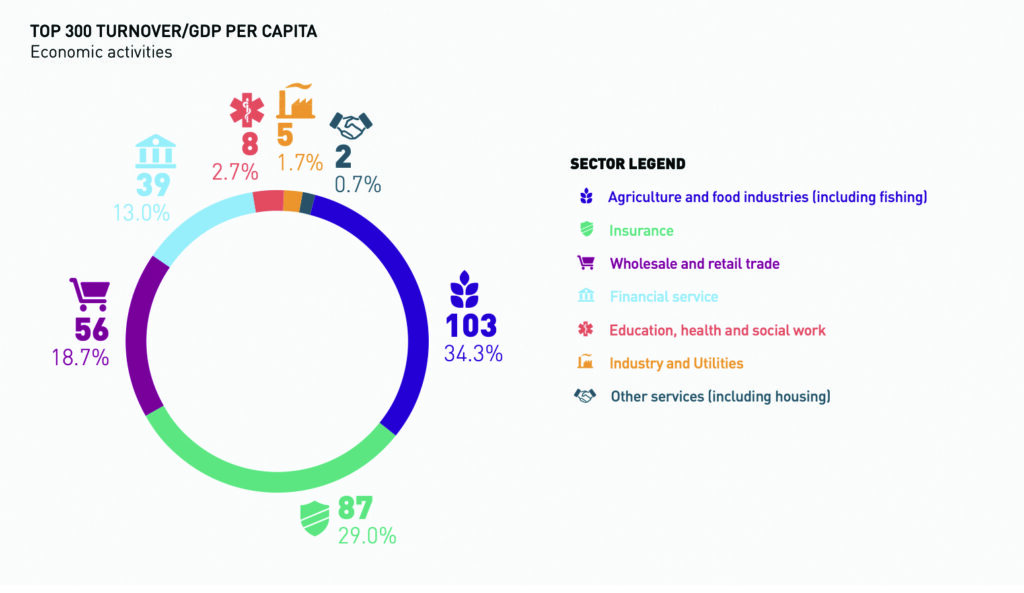

According to the World Co-operative Monitor’s data the economic activity by the 300 largest global co-ops in 2021 breaks down such that it occurs mainly in what would be seen as the private sector. Only 2.7% occurs in education, health and social care which are dominated in advanced democracies (broadly OECD countries) by public or state regulation and financing and in many cases direct provision.

Three caveats. First, these figures may distort the real picture somewhat as they are based only on the biggest 300 co-operatives. Some sectors may have many smaller, rather than large, co-ops. Nevertheless, they probably paint a broadly correct picture of where co-ops are most active.

Related: Doubling the co-op sector – where will the growth come from?

Second, none of these sectoral breakdowns are purely private or public sector. In the USA, for example, around half of health economic activity is private and about the same public (as a percentage of GDP).

Third, the public sector – or rather public spending – in OECD states is roughly equivalent to 40% of GDP, but only about half of this goes into the production of services or goods – so about 20%. The rest is redistributive transfers. Co-ops are of course mostly about producing services or goods.

In his first book, Humanizing, Restakis considers towards the end an important issue that is rarely discussed in the modern co-operative movement – just how big should co-operatives, and wider social economy, be in the whole economy? The often unspoken assumption is just that co-operatives are a ‘good thing’, and the more the better. Restakis begs to differ.

He suggests, I think correctly, that models of human economic institutions can embed three principles:

- efficiency, which minimises waste of resources;

- equity, which is the basis of economic and social justice; and

- reciprocity, which is the basis of human solidarity.

Restakis goes on to claim that “each of these principles has found its most developed expression in very different economic forms.

The principle of economic efficiency is most embodied in the conventional capitalist enterprise; equity is embodied in the policies and institutions of government; and reciprocity has found its most developed expression in co-operatives and other social economy organisations.”

But, and this crucial, Restakis emphasises two import points: firstly (and this will be controversial for some co-operators) none of these three principles, or their embodiment in institutions, is inherently better than the others.

From this idea flows important policy implications. Societies or polities that try to impose just one principle and form on the whole of society are likely to fail. Even co-operation can become oppressive.

Related: Social economy is crucial to local growth, says Power to Change

The examples of forced collectivisation of agriculture in the Soviet Union in the 1930s or forced imposition of Agricultural Producers’ Co-operatives in China under Mao’s Great Leap Forward. And in more recent times, we have seen what happened to Yugoslavia, despite the widespread imposition of so-called ‘workers’ self-management’.

Instead, Restakis argues for a balanced economy and institutions representing all three principles. Rather like, I would suggest, the mixed economy popular in western European democracies after World War II – which were broadly supported by both social democratic and Christian democratic political forces. What might, with the inclusion of an much expanded co-operative and social sector be called a ‘plural economy’?

Restakis also points out that all three primary forms (capitalist enterprise, government, co-operatives) incorporate all three principles to some degree. It’s just that each gives primacy to just one principle.

This has become more evident recently as it’s been noticed that some capitalist enterprises that have adopted at least some principles and practices of equity and reciprocity – for example in Japan or Scandinavia – have thrived.

The title of Rastakis’s second book, Civilizing the State, represents more a change of emphasis than an altogether different approach. While most of the first book concentrated on expanding reciprocity and co-operation in the capitalist sector of the economy it also addressed to some issues like social and health care, areas more likely to be subject to state provision in the post WWII advanced economies.

Chapter 10 sums up the broad approach – from Welfare State to Partner State. The whole book is essentially about increasing the role of reciprocity and co-operative organisation in the provision of state services. And this is the very opposite of the increase in private sector efficiency applied to such services over recent decades under what has commonly been labelled ‘new public management’.

Restakis argues that bringing principles of co-operation, social reciprocity and more democracy into what are usually thought of as ‘public (state) services’ could help to recharge politics and rescue them from the creeping populism and cynicism that have been obvious recently. Reclaiming politics for the common good, indeed.

If you can, read both these books. They are both informative and thought-provoking. And I think pose some interesting questions about purpose and strategy for the co-operative movement about where we want the movement, and society, to get to.