Civilising Rural Ireland by Patrick Doyle – Hallsworth research fellow at the University of Manchester – looks at introduction of co-operative societies into the Irish countryside from the late 19th century – and the influence of the movement on the emerging nation state. Here, he discusses the co-operative transformation of the Irish countryside …

Civilising Rural Ireland presents a study of a movement that shaped the social, economic, and political fabric of modern Ireland. Tracing the introduction of agricultural co-operative societies to an Ireland that experienced social unrest, violence, and eventual political independence, the book looks at the lives of ordinary men and women who joined the movement started a revolution in the countryside.

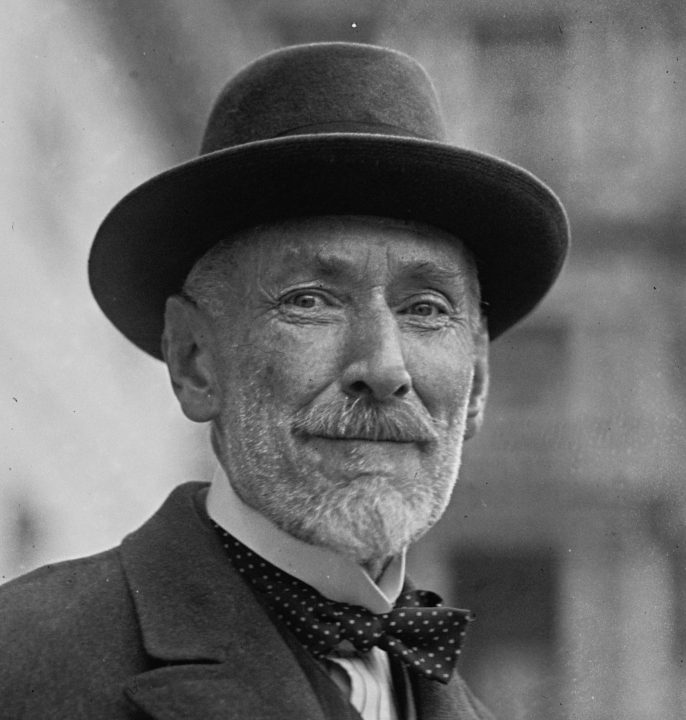

The establishment of the Irish co-operative movement in the late 19th century transformed rural society. Led by the Irish social reformer, Horace Plunkett, promoted by the poetic visionary George William Russell (also known as Æ), and with origins firmly located within a wider Irish cultural revival, the co-operative movement’s objectives went far beyond the creation of new businesses in the countryside – it aimed at a social revolution.

For Plunkett, the Irish Question was not just about politics. He witnessed the polarisation of political camps in Ireland between nationalism and unionism with distress. Instead he framed the Irish Question as an economic one.

He wrote: “The Irish Question is, then, the problem of a national existence, chiefly an agricultural existence, in Ireland. To outside observers it is the question of rural life, a question which is assuming a social and economic importance and interest of the most intense character, not only for Ireland North and South, but for almost the whole civilised world.”

The co-operative movement, he argued, offered the basis for a more positive ordering of social relations within Ireland. Co-operative creameries, credit societies, and agricultural stores modernised agriculture, but also paved the way for a more democratic economy that placed ownership of agribusiness directly in the hands of farmers.

The book traces, among other things, how farmers overcame opposition to the establishment of co-operative businesses from local traders, private creamery owners, and politicians and even managed to survive a campaign of co-ordinated attacks from Crown forces during the disturbed years of 1920 and 1921 – a period known as the War of Independence.

Importantly, the book also recounts how the growth of the Irish agricultural co-operative movement exerted a profound effect on the movement in Britain under the leadership of the Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS). Almost immediately after the first co-operative creamery was established, a new source of tension emerged between Irish and British co-operators to add to the long list of strains that have existed on these islands.

The CWS operated several depots in Ireland, buying as it did the produce of Irish farmers –especially butter – to supply the hundreds of co-operative shops that existed throughout the UK in the late 19th century. The CWS’s focus on attaining the cheapest price possible in order to pass savings onto members in Britain’s towns and cities came at a cost to Irish farmers. Irish produce proved so central to the working of British co-operative businesses that Percy Redfern, the first historian of the British co-operative movement commented that the CWS “grew fat on butter and Ireland was the source of the supply”.

The introduction of the creamery separator and competition from farmers in Denmark incentivised the CWS’s greater involvement in the production process in order to benefit their membership base. Thus, the first co-operative creamery was organised on behalf of the CWS in Drumcollogher, County Limerick, in 1889. The principal figures behind its establishment were WL Stokes, who worked as the CWS’s Limerick agent, and butter merchant, Robert Gibson.

When Horace Plunkett established the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS) in Dublin in 1894, a race to become the chief organisational force of co-operators across Ireland began in earnest and very quickly became toxic. Under the IAOS Irish co-operators looked to maximise the return to farmers and therefore looked to sell the same produce at as high a price as possible. The interests of producer and consumer – both defined as co-operators – proved to be somewhat incompatible.

An ideological fracture between the IAOS and CWS soon erupted when each attempted to gain control of the creamery sector and over a decade of hostility and economic rivalry played out across the Irish countryside – directing resources from both movements that might otherwise have helped to build on both organisations’ achievements.

In August 1901, Plunkett presided over the National Co-operative Festival at Crystal Palace and used the platform to attack the involvement of the British co-operative movement in Ireland. In front of delegates gathered from across the UK, Plunkett argued that the British version of creamery organisation offered little in the way of the co-operative spirit when applied to Ireland. The CWS creameries saw “farmers supply their milk as they do to any other capitalist who gives them their price, but in which they have no share in either management or profit, in which they take no pride, in which they learn no lesson”.

An economic war of attrition continued for the next decade. IAOS and CWS organisers slandered one another as they tried to convince farmers join their version of the co-operative creamery. In the end the Manchester-based CWS decided to cut its losses. In 1909, the CWS ceded the territory around creameries to the IAOS, having shared, in the rather ill-spirited reflections of Redfern, “the common experience of those Englishmen who seek to pave the bogs of Ireland with good intentions”.

The book will be of interest for those readers who want to gain a deeper appreciation of the ways in which co-operators on these islands collaborated and competed with one another – and in so doing illuminates the complex and sometimes uncomfortable relationship that existed, and will continue to exist, between Ireland and Britain.