The international co-operative movement has seen a series of catastrophic failures of large scale co-operatives in recent decades, such as the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, retail co-ops in Germany, France and Atlantic Canada, banking in Austria and the near meltdown of the Co-operative Group in the UK. Yet our co-operative culture has not been one of seeking to understand the factors which are common in these events and which, if understood, could be used to prevent such collapses in the future.

When co-operatives gather from around the world, it tends to be a time of celebration. They celebrate their trading success and the impact that they have had on people’s lives across the globe.

All this is to be admired, but there is also an opportunity missed. Not all co-ops will have thrived between gatherings. Sadly, some will have hit major crises and no longer be there. When this happens the major unspoken issue is not so much an elephant in the room, but which elephants are no longer there.

A common problem

The starting point of this analysis was the similarity between the crisis experienced by the Co-operative Group in the UK and the collapse of the Canadian Wheat Pools. Two very different forms of co-ops in two very different cultures, but the analysis

of why one failed gave significant insights into the failings of the other.

To prepare we looked at a wider range of failures: French retail co-ops, Austrian banking, German retailing, Canadian wholesaling, Belgian retailing, British dairying and Austrian retailing, to name but a few. It is not the intention of this paper to provide a detailed history of these, but to ask two simple questions:

1. What are the common factors that are seen in these failures?

2. How can we look for the warning signs to prevent similar failures in the future?

Big co-ops do not always end in the same way when they fail. Some collapse completely, some are demutualised, while others survive in a reduced form. Yet, in most cases, their collapse results in a massive loss of member assets and the loss of employment of large numbers of people.

We would argue that there are five common factors and that these are best understood working backwards from the moment of collapse rather than working forward. For, as Steve Jobs once said: “You can’t connect the dots looking forward.”

Major co-ops ‘do not go gentle into that good night’. Their final gasps for breath are a violent attempt to put off what is seen as inevitable by outsiders

Factor Five:

The final roll of the dice

Major co-ops “do not go gentle into that good night”. Their final gasps for breath are a violent attempt to put off what is seen as inevitable by outsiders.

Their final years are spent on a series of acquisitions, mergers and restructures. Which form this takes varies, but in all cases there is a final move, portrayed as bold and ground-breaking by management at the time. There is a language of showing other co-operatives how it should be done.

All of these fail to solve the problems they face and hasten their end. Why, when other co-operatives and businesses adopt these approaches and thrive, do these fail? It is not the tactics that are at fault, but the mindset that has already taken place in Factor Four.

Factor Four: Overconfidence

Hindsight lets us see that these final acts were doomed as they will normally be seen to have put too high a value on mergers and acquisitions and to have significantly underestimated the challenges to be overcome.

Murray Fulton’s paper on the Wheat Pools places the blame for this firmly on CEO Hubris – excessive pride or self confidence. He says: “Hubris means that CEOs have an overwhelming presumption that their high valuation of a takeover target is correct, even when it is not. … CEOs will tend to overpay for these acquisitions, and so the investments will often be unsuccessful.”

The management of these co-operatives exhibit significant overconfidence in their ability to turn the situation around. They

will overvalue acquisitions and underestimate the complexity of the tasks needed. A culture is visible in which they see their thinking as superior to their peers and to the members of their own co-op. Thus this overconfidence is combined with a culture that dismisses any voices challenging the wisdom of their moves.

Factor Three:

Lack of board oversight

None of this would be possible without a lack of board oversight. Murray Fulton wrote: “The relationship between CEO hubris and acquisition premium is greater when board vigilance is lacking— i.e., the less oversight by the board, the greater the overpayment.”

Boards in these failed co-ops fail to develop a relationship with their management which gave a clear values base for the organisation, a clear strategic direction linked to the needs of their members and a proper evaluation system of mergers, acquisitions and investments.

Lord Myners, in his report on the failings of the Co-operative Group in the UK, was scathing of the quality of its board system. “It places individuals who do not possess the requisite skills and experience into positions where their lack of understanding prevents them from exercising the necessary oversight of the executive,” he said.

Often such failings will be described as a governance failure, but it is important to see them as a failure of governance culture.

The governance system was often in place in these organisations, but Directors failed to use it to exercise the proper levels of oversight.

Factor Two:

The Wrong People

This fatal combination of management hubris and lack of board oversight develops when the wrong people are elected and recruited. Put simply, board members who fail to understand their role in a co-operative appointing managers who have thinly concealed contempt for co-operative values.

Recent failures, most notably in the UK, have resulted in greater discussion on the competence of elected representatives.

This debate is to be welcomed providing competence is defined as competence in the commercial, co-operative and social needs of the co-operative.

It is easy to point fingers at the directors of failed co-ops, but far harder to come up with how the selection process could be improved. It is unlikely to have one single solution, but to be a combination of more rigorous election processes, greater access to co-operative education, drawing from a wider pool of members and stronger support once elected.

The same can be said of the recruitment of managers. Directors who espouse co-operative values seem all too willing to appoint people who don’t and who demonstrate little appetite for building solutions through the co-operative identity of their organisation rather than importing mainstream solutions.

A look across the failures also challenges the perception that it is “outsiders” that bring co-ops down. Many of the managers rose through the ranks but remain untouched by co-operative thinking, while some from outside grasped the need for distinctive co-operative solutions.

Factor One:

Seeing co-operation as the problem

The root of the other four factors is a failure to believe in and understand the nature of a co-op. The earliest sign is a co-operative which sees being a co-op as a problem, not a solution. The feeling that their co-op identity is a burden, not a source of pride appears to precede the other four factors. A cynicism about co-operative democracy and member engagement can develop long before the actions which cause the eventual collapse. In many ways, looking for this is the canary in a coal mine.

If not rooted out by active co-operative promotion and education, it will fester and grow into the other factors.

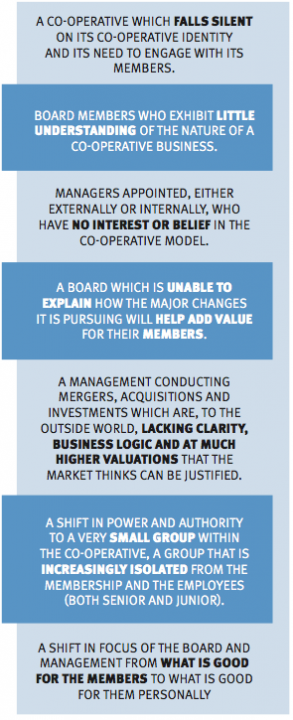

The Early Warning Signs

The most depressing part of these collapses is not that they follow very similar paths, but that the warning signs were there for all to see. These signs are:

It is never too late to act, but acting on the earlier signs rather than waiting for the inevitable can dramatically reduce the loss of member value and increase the chance of survival.

It can also reduce the damage to the movement of yet another co-op going down in flames. This is why it is everyone’s business to raise the alarm when these signs are visible.

Co-operatives do fail, and we need to be able to acknowledge this and talk about it in a serious and thought-provoking way, in everything from global conferences to day-to-day conversations.

In short, the antidote to the problem is to ensure that there is a conversation about the value of co-operation and the role that we can all play in unlocking it.

Further Reading:

Fulton, Murray E, and Kathy Larson, 2009

The Restructuring of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool: Overconfidence and Agency Journal of Co-operatives 23: 1–19

Fulton, Murray E, and Kathy Larson, 2009

Overconfidence and Hubris: The Demise of Agricultural Co-operatives in Western Canada. Journal of Rural Cooperation 37(2): 166-200