This is a story about how a coffee co-operative brought a community together – and how the co-op reinvented itself after the actions of a corrupt leader. It’s about cross-continent collaboration and the world’s love of speciality coffee. It’s a story of collaboration and resilience. And it starts in New York, on 11 September 2001.

Among those fleeing the devastating attacks on the World Trade Center was JJ Keki, a Ugandan Jew, coffee farmer and musician. Learning that the September 11 attacks were religious-motivated violence, Keki worried that similar attacks could happen in Uganda. He told an interview with the National Catholic Reporter (NCR) that he had to do something constructive.

The story moves to the town of Mbale, eastern Uganda, an agricultural trade centre on the edge of the Mount Elgon National Park. Most people in the country are Christian (80%) or Muslim (12%). Uganda’s Jewish community (approximately 2,000 members) is mainly concentrated in Mbale – where Keki is from.

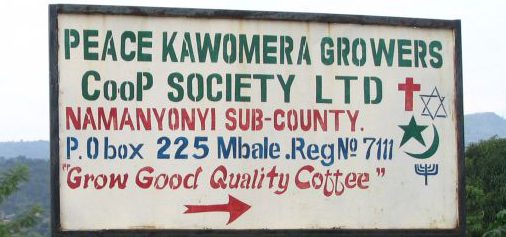

When he returned from his trip to New York, he enlisted over 1,000 local Jewish, Christian, and Muslim farmers to form a co-operative, Mirembe Kawomera (‘Delicious Peace’) – the first interfaith coffee co-op of its kind in the world.

Since the co-op launched, there has been a working relationship between the different religions, Samuel Ngugo, a Protestant who served as the co-operative’s inaugural treasurer, told the same NCR interview.

Elias Hasulube, a Muslim who served as a manager and senior field officer, said there hadn’t been problems between the faiths but they hadn’t been working together in this way. The coffee co-operative also spurred community growth, supporting primary schools from all three religions.

The co-op received marketing support from Jewish charity Kulanu (‘All of Us’). Laura Wetzler, a folk singer who was volunteering at the time, rang a long list of speciality coffee roasters, until she reached Thanksgiving Coffee. And here our story jumps to California, where Thanksgiving CEO Paul Katzeff took the call, and saw the beauty in a story that needed to be told.

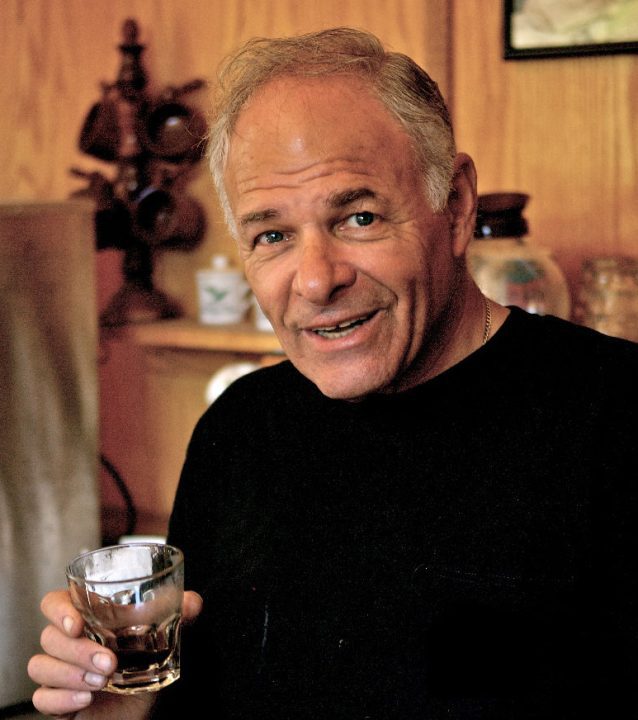

Katzeff, now 86 and mostly retired, began his career as a social worker – and in 1972 set up a coffee roasting operation on California’s Mendocino Coast with his wife, Joan. “We didn’t start out to change the world,” he says, “we were just looking for a good cup of coffee. Not just a cup, but a just cup.”

But he felt the story of Jews, Christians and Muslims working together and enabling economic development was an important one.

“This was a really big story that the world needed to hear. We began to promote the idea of an interfaith co-op. I went to Uganda and met the co-op, and we began to sell its coffee to interfaith religious organisations, churches, mosques and synagogues.

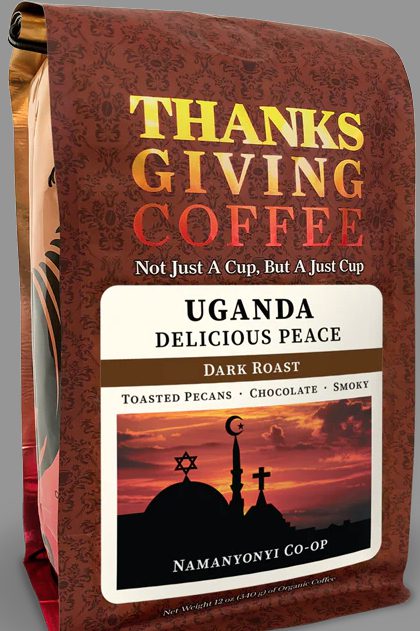

The coffee was branded Delicious Peace, and for the next decade, Thanksgiving Coffee was Mirembe Kawomera’s sole buyer. They ran a rebate programme, where $1 from every package sold was put into a trust account, which was then returned to the co-op. In 2008 it was honoured by Tufts University with the prestigious Jean Mayer Award for Interfaith Work.

But co-operatives are not infallible, and things began to fracture.

In 2009, Thanksgiving Coffee had been approached by an east coast organisation working for tolerance and better understanding in areas of conflict, with a request to distribute Delicious Peace using a private label programme; Thanksgiving declined. A few years later, a shipment they were expecting from Mirembe Kawomera was delayed by eight months.

In 2104, on the back of this, Katzeff and Nicholas Hoskyns of Etico (an import/export company he works with) visited Uganda – and discovered the co-op’s leaders were secretly selling coffee to the east coast company for $100,000 instead of the $75,000 agreed by Thanksgiving (which itself was 50 cents a pound more than the price at the time). This company had also sent a film crew to Mbale, armed with a script, to reposition themselves as the author of the co-op’s story.

This was the beginning of the end for Mirembe Kawomera – but not the end of interfaith co-operation.

“Keki had done this without the board’s knowledge,” says Katzeff. “We weren’t going to abandon the farmers. They didn’t do this. The leader did it. So I said to the farmers, ‘form another co-op, get rid of this guy, and I will continue buying coffee from you.”

Keki was removed from the board under a cloud of fraud and embezzlement. He left with money and land belonging to the co-op, which itself lost its Fairtrade and organic certification.

Mirembe Kawomera disbanded in 2016, but a new co-op rose from the ashes, with 200 farmer members, again from different faiths. The Namanyonyi Community of Shalom Coffee Cooperative was born, its name a nod to the Communities of Shalom charity, which provided training to the new co-op’s directors, funded by Thanksgiving. Through Namanyonyi, the farmers have regained Fairtrade and organic certification, and continues to supply Thanksgiving Coffee.

Does Katzeff think being a co-operative helped or hindered the situation in Mbale? “Both. It helped because it enabled farmers to pull together enough coffee to export, get Fairtrade and certification, and overcome differences.

“But it also hindered, because the leadership that remained had been under Keki’s thumb for ages. He was a powerful leader with an ideology that was very self-serving.” Today Keki still retains control of some of the original co-op’s land; any attempts to reclaim it are met by resistance – and machetes.

“We are still trying to figure out how to best help this co-op survive long-term,” says Katzeff. “We love this story of multiple faiths helping each other, moving beyond personal beliefs. And we’re seeing women’s issues being discussed more among Muslims and Jews. Yes there has been corruption, but there’s also resilience.”

Alongside this, Katzeff is conscious of “interfering in a culture that I didn’t understand and creating something that might come back to haunt me as a white privileged man”.

“But the important thing for me is to keep trying to make a difference.”

For him, that difference is intimately tied to quality of life; which in Uganda is underpinned by water quality.

“Not having access to safe water is the number two killer of children under five worldwide. Out of Uganda’s population of 45 million people, 38 million people (83% of the population) lack access to a reliable, safely managed source of water,” he says. “We did a preliminary study a few years back and found that between 50-60% of the money that was being sent to the co-op and its farmer members was spent on healthcare for waterborne diseases like typhoid, cholera and dysentery.”

To this end, Thanksgiving set a new goal: to provide clean water for every family of the Namanyoni Co-op. “To accomplish this we partnered with Spouts of Water, which creates sustainable clean water filters out of local materials and hires local employees. These filters allow the farmers and their families to drink and cook with water safely without boiling it first, saving the surrounding forest environment as wood is the primary source of cooking heat, with the added benefit of saving the many hours needed to harvest firewood.”

Katzeff adds: “Cutting waterborne diseases massively increases disposable income for the farmers, without raising the price for coffee companies buying the coffee at the end market (roasters) who are being squeezed by companies like Starbucks and Peet’s.

“By lowering the cost of living, roasters who just can’t afford to pay co-operatives more for coffee can, by subsidising clean water filters for every household, increase disposable income by up to 50% (in our experience). For a one-time cost of US$24 per household we accomplished a 50% increase in disposable income, supported healthy forest growth and decreased stress in the community while making sure farmers save the money they need to thrive with the added benefit of increasing health and happiness in the community and for each family.”

Katzeff himself has initiated several changes throughout his career, particularly during his time on the board and as president of the Specialty Coffee Association, where he established the organisation’s first Environment Committee in 1996 (now named the Sustainability Committee).

In 2000, with a $400,000 USAID grant to Thanksgiving Coffee Company, Katzeff travelled to Nicaragua and led a project to develop cupping labs at nine first-level primary co-ops. The project trained 65 Nicaraguan cuppers, who become the first farmer specialists in evaluating the taste and aroma of coffee.

These were the first farmer-owned, at origin, cupping labs, which enabled the co-operatives to taste and evaluate the quality of their farmers’ coffees which provided the knowledge which enabled quality improvement and increased their coffees commercial value. It levelled the playing field between buyers and sellers.

The concept is now part of the infrastructure of the coffee industry worldwide.