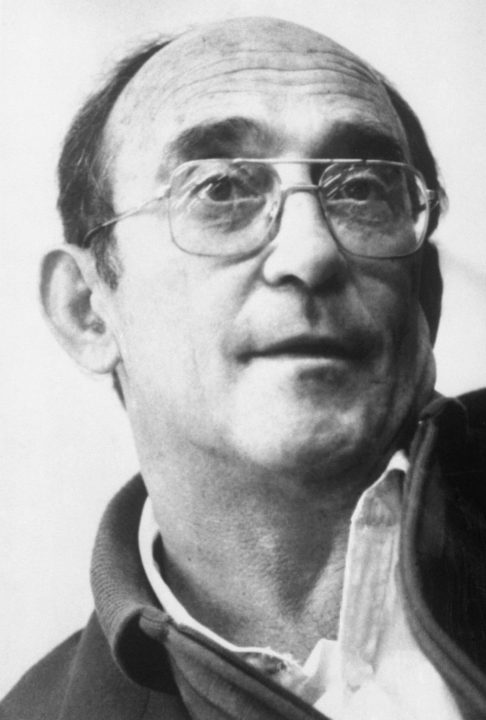

Denis Theodore Goldberg (11 April 1933 – 29 April 2020) was a South African social campaigner who was active in the struggle against apartheid.

He was accused No. 3 – and the only white man – in the Rivonia Trial, alongside Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, and was imprisoned for 22 years. He was released in 1985 and moved to London, continuing his campaign, until the apartheid system was fully abolished with the 1994 election. He returned to South Africa in 2002 and founded the non-profit Denis Goldberg Legacy Foundation Trust in 2015. He was diagnosed with lung cancer in July 2019, and died in Cape Town on 29 April 2020.

His wife, Esmé, and their two children had come to the UK in the mid 60s – and had become very active in the Woodcraft Folk. In his autobiography, A Life for Freedom, Denis wrote: “This organisation of 30,000 people, parents and children, took Esmé and our children under their wing when they arrived in Britain. Esmé made many good friends, and the Folk, as they always called themselves, became ever more connected to anti-racism issues and opposed apartheid in every way they could, especially through the boycott of South African fruit. The co-operative retail movement supported the Folk, who in turn demanded that the co-operative movement, with its many retail stores, stop selling South African fruit.”

Denis spoke at many Woodcraft Folk meetings and annual conferences. He was asked to stand for election as president, he said, “because some members wanted to overcome the encrusted organisational structures and make room for new ideas”. He agreed to stand, provided that he could function as an honorary president – and was elected with a majority of just one vote.

“I did not play an active role,” he wrote, “but I was able to raise issues such as their use of pseudo–Native American (‘Redskin’) greetings and doggerel. Having lived under apartheid, I believed that even though they meant well, and the founders in the 1920s intended to honour the ‘noble savages’ who lived in harmony with their natural habitat, these figures of speech represented an undignified way of treating people of colour. Slowly others took up the issue, and it was good that it became widely debated. I was happy to step down when the Folk decided to appoint long-time members as honorary life presidents.”

He added: “[The Woodcraft Folk] is a wonderful organisation that opens young people to collective action and awareness of social questions. One of the great moments in Woodcraft Folk history was the saving of hundreds of young people from the Nazis in the 1930s and getting them to safety in Britain. They are my kind of people.”

Doug Bourn, who was national secretary of the Woodcraft Folk (1983 – 1990) and is now professor of development education at the University College London – Institute of Education, says of Denis: “I had the great privilege to meet and get to know Denis during the 1980s upon his release from prison. He made an important contribution to the Folk in reminding us all of the importance of international friendship and solidarity. It was a result of his inspiration that many of us began to encourage and support more international solidarity activities and exchanges. He was also conscious of the important role the Folk had played for his family during his time in prison.”

Adrienne Lowe, who was chair of the Woodcraft Folk National Council (1992 – 1995) and currently sits on the Co-op Group’s National Members’ Council, remembers stories about Esmé and Denis from when she first joined the Woodcraft Folk in Wimbledon. “I learnt about him and his role in rising up against apartheid in South Africa,” she says. “The Folk took actions against the South African regime by banning South African goods from camps. Even though it was written clearly on food order forms to the Co-op, the occasional crate of oranges would somehow get through only to be duly returned. As a teenager, I took part in anti-apartheid rallies in London and joined the picket line outside South Africa House narrowly avoiding being arrested as those around me were.”

After Denis’ release from prison he attended the Woodcraft Folk’s annual conference at Loughborough University, where he “kept us all spellbound by his inspirational address,” says Ms Lowe. “Even after 22 years in prison, he was not bitter or jaded. He was as determined as ever to see an end to racial discrimination in South Africa and would spend as long as necessary working within the ANC to achieve this. His motivational speech left me in awe of such a great orator who really believed in equality, tolerance and mutual respect.”

She remembers Denis Goldberg accepting the Woodcraft Folk presidency “reluctantly, as he was not into grandiosity”. She adds: “I was chair of National Council 1992 – 1995 and although Denis did not attend many meetings, he and I became firm friends, offering his support and enthusiasm when requested. During this time, South Africa eventually had its first multi-racial elections, which saw Nelson Mandela lead the ANC to victory and Denis’ dream towards racial equality take off. Closer to home, international work continued to flourish and at the International Camp in 1995 in the New Forest, which Denis visited for a few days, he was amazed at how 3,500 people could live together supporting the values and principles he held so dear to him.”

The Woodcraft Folk also supported Community HEART project, launched at South Africa House, designed to assist other initiatives in health, education and training in the newly emerging South Africa. “The Folk’s response was an initiative called A Book and 10p, where people were asked to donate a book to help stock schools and libraries and the 10p was to cover the shipping costs,” says Ms Lowe. “I recall a couple of fun-packed Sundays unloading boxes into Denis and Esmé’s already bulging garage.”

She adds: “Over the next few years, Denis and I were to meet up at book launches, Co-op Congress, Burns’ night suppers and the like, even though he had moved initially to Germany and then back to his native South Africa. When we met he was always keen to share his latest ideas, including one based on using art and music as a medium for promoting social equality, hence his idea for his latest project, the House of Hope.

“Denis did not live to see the building of the House of Hope but his legacy will ensure that it does happen in Hout Bay where he chose to live out his days. His memory will be one of a new South Africa where people come together to enjoy their lives.

“Anyone who met Denis could not fail to notice his keen sense of humour, his optimistic approach to new ideas, his politeness (even if he didn’t agree with you!), his humility and his love of humankind. To quote himself: ‘Never ever give up hope! Never! Ever!’

“Rest in peace, my friend.”

Thank you to Adrienne Lowe from the Woodcraft Folk for the additional information used in this orbitary.