There is much frustration within the co-operative movement that few people know about the model beyond food stores and funeralcare.

It is not on the syllabus of most business schools, and unless you live near, work for, engage with or stumble across independent co-ops, they are hard to find. As the introduction to Co-operatives UK’s Co-operative Economy Report 2018 asked: “Despite providing solutions to so many problems, with record membership figures and demonstrating incredible resilience, why do co-ops remain the best kept business secret in the UK?”

But they are more than businesses. One educational institution showcasing the impact of co-ops to students is Manchester University, which is running an English literature module on Competition, Co-operation and Happiness: Dangerous Ideas in Victorian Britain.

Led by Dr Michael Sanders, the course starts by looking at three key ideologies of the early 19th century – political economy, utilitarianism and Owenism – before exploring some of the ways in which ideas of competition were revised later in the 19th century as a result of the ideas of John Ruskin and Charles Darwin.

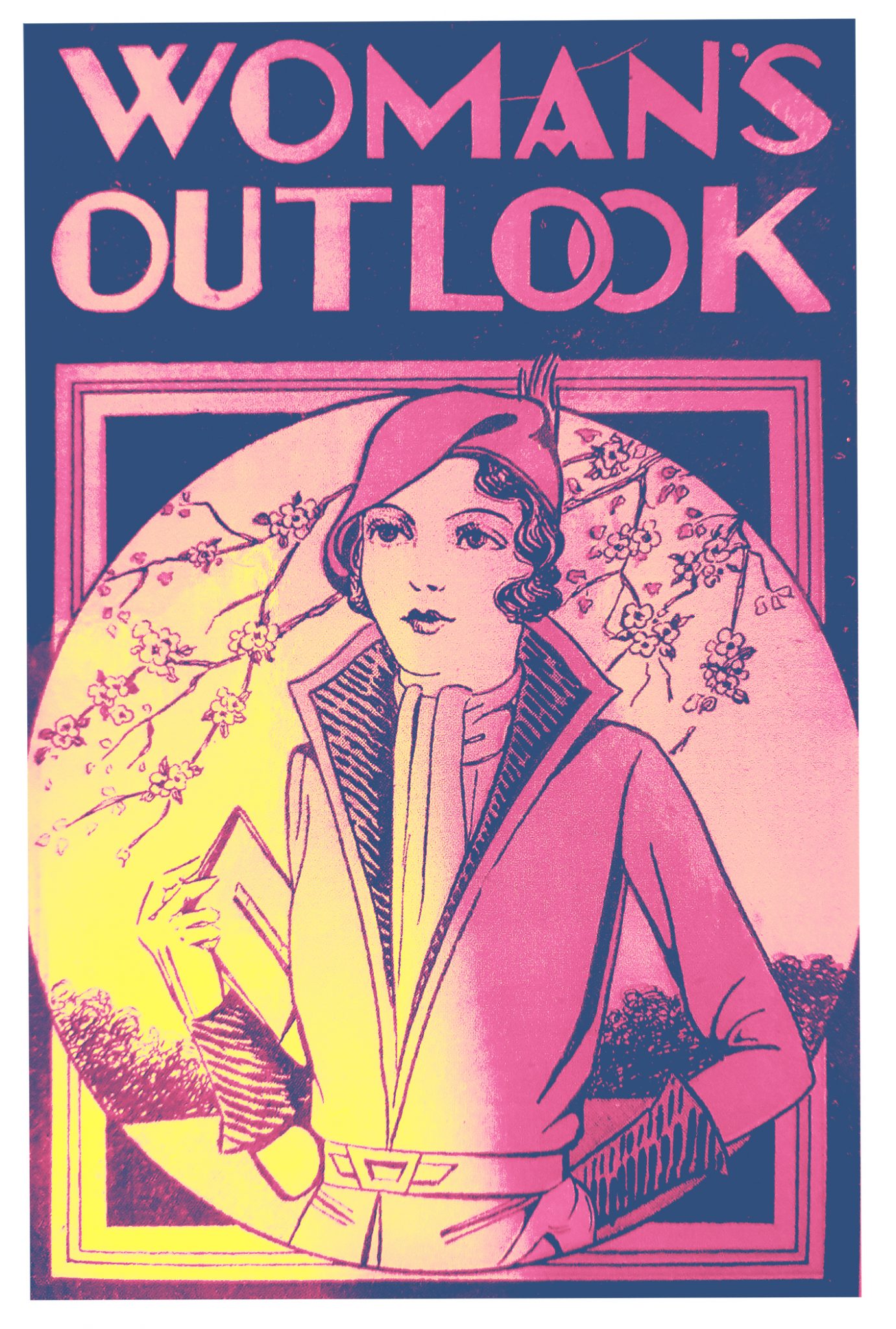

The final third of the course examines the efforts of the co-operative movement to create an alternative to the individualistic, competitive culture fostered by industrial capitalism. It looks at how this was reflected in co-operative periodicals at the time, from Our Circle (aimed at co-operative youth) and Women’s Outlook (the magazine of the Co-operative Women’s Guild) to Millgate Monthly (a cultural magazine aimed at a co-operative public) and Co-op News itself.

“I grew up in rural Devon, and even there, ʻthe Co-op’ was always part of the landscape,” says Dr Sanders. His teenage years coincided with the anti-apartheid movement, which the Co-op backed. “You could shop in the Co-op safe in the knowledge that there was no South African produce there. And then the Co-op suddenly changes from being just another shop on the high street to being a shop on the high street that was a little bit different.”

From that early political awakening, he became interested in the Chartist movement and other aspects of working class history. “The great working class success story of the 19th century is the co-operative movement,” he says. “That story of how 24 men from Rochdale changed the world is just mind blowing and it spins off in so many different directions. I thought: ʻI’ve got to find a way of teaching this’.”

Dr Sanders wanted to do something positive, away from the ʻheroic defeat’ stories labour history events are, in his view, often relegated to – while making it contemporary and relevant.

“The thing about Victorian literature is that it’s not a rear view mirror,” says Dr Sanders. “It’s still with us, still shaping us and actually it might be the future. Take precarity. Yes in a sense it’s a new problem, but if you study 19th century working practices, precarity was the name of the game.”

He was interested to see if there was a way of bringing classical Victorian literature into a meaningful relationship with the co-operative movement: “So much middle-class Victorian literature is imbued with the idea of competition and competitive culture – and on the other side we’ve got co-operatives and co-operative culture. Both of them make claims that they’re concerned with human happiness.”

One of the publications students find most interesting is Our Circle, which ran from 1907 to 1960. It was a magazine aimed at young children and teenagers containing informative articles (for example on the lives of prominent co-operators) alongside short stories, puzzles and lessons in Esperanto – a universal language that was popular within the co-operative movement.

Related: A century of education, social change and the Co-operative College

Dr Sanders says: “The students had a really interesting discussion about what they thought the age range was. The very first issue looked like it was trying to cover ages 8-18. By 1926 it’s more 12-18 and by 1936 it’s almost 14-20. There’s a lot of interactivity [between the magazine and its readers] – there’s a real sense of Our Circle saying ʻWhat do you want? Tell us what you are interested in. We’d like to know.’

“In comparison, Millgate Monthly was almost aspirational, more concerned with the distribution of cultural capital: ʻThis is what we think co-operators should look like’.”

He believes that a “whole, genuine culture around co-operative societies has been lost.” While a few examples remain, societies ran sports clubs, choral societies, brass bands and day trips for colleagues and members.

“If you read some of the debates in the 1950s, you can see the Co-op, in a sense, start to lose its way a little bit,” says Dr Sanders. “One of the ways I think it does that is that ceases to take culture – and that education mission – as seriously as it once did.

“This coincided with the Co-op becoming aware that it needed business expertise from outside the movement. But it forgets that previously its management had risen through the ranks, and therefore imbibed co-operative culture, values and ethos from the start – they were steeped in it. The people coming in weren’t malignant or vindictive, they just hadn’t been raised in it. So the culture begins to change.

“Another great missed opportunity was not having the Co-operative Women’s Guild on the board of the CWS, despite them saying on numerous occasions, ‘we are your main purchasers, we are your main customers, we can tell you about the products you’re making’.”

The course ends with the students undertaking an individual research project on some aspect of co-operative culture, such as looking at the extent to which gender and class intersect with the ideas of competition, co-operation and happiness.

“The project requires them to find something in the co-op periodicals that they’re interested in. The brief is to take four issues and design a précis and an analysis to go alongside it.” The aim is for some of the précis to be added to the Co-operative Archive website.

Why does he think that learning about co-operatives is still important today? “Because the Co-op, from its inception and throughout its history, asks the questions that nobody else in mainstream business asks. The Co-op has a duty to its customers and its employees. But it also has a duty to the neighbourhood and environment where it’s located – and it has to find a way of balancing that. Who else in mainstream economics is thinking in these terms?”

Dr Sanders adds: “The initial proposition of the Rochdale Pioneers was: ‘we can do this ourselves’. And that’s what I really want my students to take away. This isn’t a history of high-powered intellectuals of incredible experts, this is a story of ordinary men and women. It’s the everyday democracy and the sense that everyone has a contribution to make.

“If a group of weavers in Rochdale deprived of formal education, in the 1840s, can make a success of it, then given the advantages we enjoy in terms of education and basic prosperity, you feel we should be making a much better job of it than we are.”