British Black History Month was started in October 1987 by Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, who was working as special projects officer for the Greater London Council. Following a visit to the United States where a similar event were marked in February, he campaigned for a UK version to help reduce racial tensions which had been building among younger generations.

Over the years, the idea spread beyond London and became part of the national agenda. Museums and archives adopted it enthusiastically to focus on objects or stories from their collections through the perspective of racial identity. But it was initially a mixed bag, as some institutions felt less equipped to respond authentically or authoritatively – either because they didn’t feel their collections adequately reflected this history or because of sensitivities around difficult subjects.

Although Black History Month looks at different themes each year, its original purpose was to promote and celebrate the contributions Black people have made to British society. In the 1980s and 1990s most of the published or public ‘Black History’ available was focused on the experiences of slavery and inequality, particularly in the United States, and this became an area of increasing discomfort for those constructing a public narrative – with many organisations instead preferring to focus on more positive stories and, in particular, personal achievements.

Telling these stories can be difficult because of the ‘hidden’ nature of the roles and experiences of people who identify with Black History. This difficulty can be compounded by a fear of ‘getting it wrong’, not wanting to focus on ‘bad history’ or speaking on behalf of others. The danger of not engaging is that it remains hidden or invisible because we are concerned with only talking about what is seen as ‘good’ history. Another obstacle has been the unwillingness to focus on Black History Month due to concerns about such efforts being seen as ‘tokenistic’.

So, what about the British co-operative movement? Where do we stand in all of this?

The Co-operative Heritage Trust was formed as a charity to take care of what remained of the movement’s history in physical form (objects made for and by co-op societies) as well as what had been documented as important to the movement. Even though thousands of independent co-operatives started off in the grocery trade, the point of them was really to offer members a vehicle for improvement and the chance to be educated in order to elevate the rights of working-class communities in a starkly unequal and exploitative society. The values and principles formed in 19th Century Rochdale would be the framework for a support network for communities, which would allow them to campaign for social and political change, and later offer new opportunities for community ownership of assets and different models of employment.

Related: UK Black History Month: ‘Co-ops should Rise to the occasion’

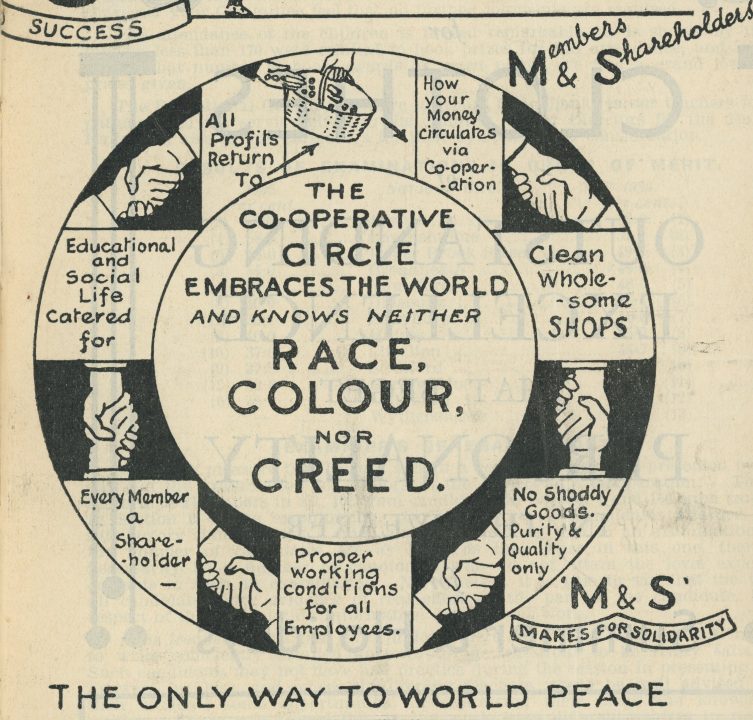

Giving working people a voice naturally meant going against the capitalist narrative and class structure, and was radical in the approach to equality of experience regardless of background or belief. The original photo of the remaining Pioneers in 1865 is of older white men: there are no women or any people of colour, and there are no clues to the ethnicity or personal beliefs of early membership, so it is easy to assume that there was racial hegemony.

Statistically it is impossible for there to have been no people of colour in Rochdale and other early co-op towns at the time, but names alone don’t help us with visibility – and even the Pioneers themselves were not valued for their personal contributions. It would be many years before the 28 were memorialised, with the movement favouring the power of the collective over the individual. Despite this, the nature of the movement was such that it should come as no surprise that those who started co-ops were often involved in wider campaigns such as the abolition of slavery or the right for the vote.

Co-op leaders were involved with the Union and Emancipation Society of Piccadilly, Manchester, to put pressure on the United States to end slavery in the 1860s, but relationships were complicated. Manchester had made its money and power base through cheap slave-picked cotton and those who handed out pamphlets and attended lectures drank tea and coffee with sugar, and smoked tobacco. These were also the most profitable goods sold by co-operative societies which enabled them to expand their businesses and influence –and as a direct result of access to cheap sugar, the lives of white working-class communities were improved through the reduction of food poverty within a generation.

Sstudents of the Co-operative College at Ashford Grange Boarding House (1940s).

There was an understanding in the movement that sourcing ‘exotic’ goods came at a price and that doing so should not be exploitative to workers in other countries, so co-ops attempted to provide decent homes, schools and other facilities to workers overseas and use the propaganda machine to educate their members on conditions being better on their plantations and depots.

The context of this trade was, however, explicitly colonial – CWS (Co-operative Wholesale Society est 1863) sent their agents and managers to depots in Africa in 1912 to establish relationships with governors and ensure that their supplies and prices could be maintained for the benefit of the societies who were their members. There are some rare photographs of a deputation to West Africa showing the agents meeting important people and tribal leaders as well as African missionaries and educators, but these have been used rarely and typically only images of the white staff have been shown. We need to look at the associated business documents to find out more information and fill in the gaps.

The solicitor working for CWS in Lagos is recorded as Kitoye Ajaso, from Sierra Leone; he had previously been known as Edmund Macauley, a name his father Thomas had been given in slavery before settling as a free man in Sierra Leone. Ajaso had studied law in Britain and formed a practice in Nigeria as well as lobby for election by founding the People’s Union of Nigeria to campaign for improvements for local people without discrimination in race and religion, and started a newspaper called the ‘Nigerian Pioneer’. However, he was considered politically conservative and complicated as he believed that Nigeria would only develop under the Imperial system. Throughout the 20th Century, international students would come to study at the Co-operative College in order to form co-ops, education centres and become leaders at home, particularly as part of the transfer from empire to independence, and helping to form the international movement as well as the state infrastructure in the post-colonial era.

So, in the ‘history of our history’, we have tended not to dwell on individuals, but that makes an emotive story harder to tell, because people more easily connect with the human experience and value the ability to put names to faces and achievements. The 200 years of our story are diverse and complicated, and most people only scratch the surface of the origin story of a collective. Typically, we only find personal stories when those individuals have already found their way into the history books independently, or when new information comes to light from relatives doing their family history – so what about all the people who remain relatively invisible in our history? How do we go about ensuring that the ‘invisibility’ doesn’t continue and that we are able to reflect more of the ways in which Black British people have contributed to our movement’s development in recent years as well as in the future?

How much does race and identity play a part in your involvement in the co-operative movement? What can you tell us about your experiences?

To record your experiences or those of your family members, contact the Co-op Heritage Trust at [email protected]