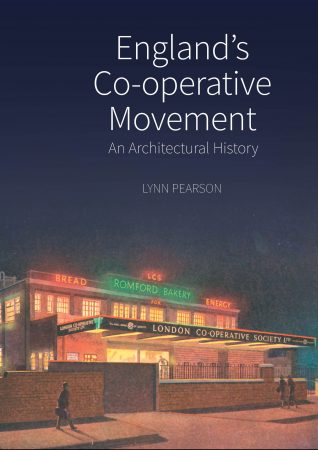

England’s Co-operative Movement (An Architectural History) Lynn Pearson (Historic England, £40)

From co-operative shops to infrastructure, for more than a century and a half the buildings of the co-operative movement have made a huge mark on England’s towns, cities and villages.

A new book by the architectural historian Dr Lynn Pearson explores how, where and why this architecture came into being. Taking a chronological approach from the pioneering retail societies of the 1840s to the present day, she presents a richly illustrated guide which contextualises buildings in relation to the expansion and changing functions of the co-operative movement.

It was whilst researching a previous book about industrial buildings that Dr Pearson realised the volume and significance of co-operative architecture. An independent researcher, she is based in Newcastle which, along with Manchester and London, once had a branch of the Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS) architects’ department. Established in Manchester in 1897 and continuing in various guises until the early 1980s, the CWS employed in-house architects who were available to independent societies around the country which were members of the CWS – although individual co-operatives could also choose to work with local or national architecture firms if they preferred.

Like Manchester, which was home to the headquarters of the CWS along with a number of factories and warehouses, Newcastle boasts a high concentration of historic co-operative buildings. These include the Discovery Museum, housed in a Victorian CWS depot, which Dr Pearson says is “still laid out pretty much as it was and very little changed from when it was a functioning warehouse”. She used to buy her dog’s biscuits in the city’s art deco central co-operative store, dating from the early 1930s, which has since been converted into a hotel, and shop in the last hypermarket to be designed by the CWS architects’ department. In spite of the familiar presence of these buildings, though, and (like a lot of people) having memories of reciting her granny’s divi number, Dr Pearson admits she “never knew quite what they meant”.

Related: How co-operative architecture has shaped Britain’s skylines

“They’re just part of the local furniture,” she explains. “You don’t realise the whole system they fitted into.”

Although they were sometimes innovative, particularly in factory design, Dr Pearson’s book is the first to focus specifically on the buildings of the co-operative movement.

“I looked for someone else’s book on the Co-op, but there wasn’t one,” she says. ‘There was a book on the buildings of the Labour movement which had a chapter about the buildings of the co-operative movement, but I realised if I wanted one I had to write it.”

One of the reasons co-operative buildings have been under-appreciated, Dr Pearson thinks, is “because they weren’t that bothered about publicity outside of expanding the co-operative movement”. She reflects: “The CWS was enormous but it was all forgotten about almost completely in a few generations. It seems like another world.”

Related: Design-build co-ops: the architecture for a new economy

Today our main experience of co-operative buildings might be popping down to the local co-op shop or using the services of a funeral home. What’s striking about Dr Pearson’s study is the broad scope and immense scale of the co-operative movement in England through much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

“I was surprised how much there was and just how big it was,” she says. “There were over 100 branches in Leeds alone, which is amazing, and quite a few are still there, even the ones that don’t look like co-ops and aren’t instantly recognisable.”

Dr Pearson shows us not just shops but the infrastructure and wider networks behind them, from bakeries, dairies and laundries to warehouses and goods depots, and the reach the co-operative movement historically had into many people’s lives.

“The movement did so much, and it covered a lot of people,” she explains. “Co-op buildings are everywhere and they’ve made such a huge contribution to our townscapes.”

Related: Documentary to tell story of Hull’s iconic co-op mural

Something that comes across strongly in the book is how adaptable co-operative societies were, from providing mobile deliveries to new estates without facilities to erecting prefabricated stores in the aftermath of the Second World War. As Dr Pearson says, “They were very good at responding to circumstances”.

They also extended and augmented existing buildings as the need arose. “The architects were very good at adding bits as they went along,” she adds. “We tend to think things were built in one go – but they weren’t.”

Co-operative societies sometimes – although not always – embraced changing styles and priorities in architecture, from solid redbrick warehouses to the sleek, streamlined modernity of 1930s buildings – which were accompanied by glamorous promotional images – to stores designed to accommodate new ways of shopping, such as self-service, and large hypermarkets, which catered to customers’ growing car use. More recently, the Co-operative Group’s current headquarters, Angel Square in Manchester, which was completed in 2013, aspired to sustainability, utilising modern and environmentally-friendly approaches to building design.

Although little in the way of records exist relating to the CWS architects’ department, the Co-op News proved to be a ripe source of historical material, reporting on societies’ plans for new buildings, or their opening events. Another rich repository was eBay – Dr Pearson amassed a large collection of postcards depicting co-operative premises, whether in construction, at the time of their opening, or giving a more personal perspective with staff posed outside. Many of these are reproduced in the book.

Dr Pearson also travelled up and down the country, visiting co-operatives large and small, in rural and urban areas. The fun part, she says, was taking photographs. This unearthed knowledge from locals keen to share information, showing the focal point co-operatives have provided in communities and the place they have in people’s memories.

Related: A co-operative rethink of our towns and cities?

“People are really interested,” she says. “When I was standing in the middle of a busy street taking photographs of a building people would come up to me. In Stoke, a chap stopped his van and said ‘my dad used to work there’. He told me a bit about the building and said the safe was up in the top of the dome in the corner.”

Whilst some co-operatives continue to operate in their original buildings, other premises have been converted to different uses: co-operatives downsized when meeting halls and libraries, which were housed above stores in the nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries in order to provide education and meeting spaces for their members, became redundant. Others were shut when societies closed or merged.

Dr Pearson would have loved to have seen inside the hall above the former premises of the Oldham Industrial Co-operative Society, built in 1900, but this wasn’t possible; although the lower floors are occupied by a commercial business, the upstairs is derelict and in a dangerous condition. She also wishes she could have seen “some of the big halls when they were all laid out for a massive banquet”.

But she did relish the opportunity to visit those buildings which were still in use, even if they were not fulfilling their original purpose. “It’s nice when you can go in co-op buildings when they’re still alive,” she says, adding that a particular favourite of hers is the Todmorden Industrial and Co-operative Society’s early twentieth-century drapery store in West Yorkshire. A rare surviving example of a co-operative shopfront designed in an art nouveau style, the building now houses a thriving bar.

In the book, we also get a glimpse into buildings which are lost, through archival photos, drawings and plans. Dr Pearson looks past bricks and mortar to give a valuable insight into the ways in which we might have experienced co-operative buildings in the past. We get a sense of changing fashions and ideas about shop layout and décor: Dr Pearson would have liked to have experienced some of the 1960s restaurants in Co-operative stores, which showed off what she describes as “interior design at its best and flashiest”. Also important is a discussion of corporate branding, as a way for the co-operative movement to attempt to assert its identity.

Equally fascinating are those designs which never made it off the drawing board. Manchester’s ‘Co-operative Quarter’ (now known as the NOMA development), which contains a cross-section of architectural eras and styles, could have looked very different if a 1971 masterplan for the area had come to fruition.

The project crossed over with another of Dr Pearson’s areas of interest: public art, a topic on which she has written extensively. A sub-section of the book is dedicated to artworks commissioned alongside buildings, including a series of murals dating from the 1950s and 1960s. A highlight for Dr Pearson was an unexpected encounter with a large, colourful mosaic running the length of the frontage of a co-operative pharmacy in Scunthorpe, opened in 1963.

“I saw the Scunthorpe mural in an article about the tenth anniversary of the building. I didn’t know it was there before,” she says. “I looked it up on Google Maps just in case it was still there and it was. I was absolutely stunned. I couldn’t quite get there and back that afternoon but I went the next day just in case it disappeared overnight. I’ve been back a couple of times since, including a birthday night out in Scunthorpe to take pictures of the mural!”

The book contextualises co-operative architecture in England with reference to buildings elsewhere in the UK and Europe. Dr Pearson would have liked to have visited international buildings connected with the CWS’s trading and distribution worldwide, but such is the richness and volume of the co-operative movement’s architectural legacy in England that there is more than enough material to fill the book. She hopes that her project might be a starting point for others to contribute further histories of co-operative architecture in other countries.

Accessible in style and timely in its publication, England’s Co-operative Movement reflects not just academic interest in the subject but public enthusiasm for twentieth-century architecture. This includes a renewed concern about the buildings of the co-operative movement from within local communities. Dr Pearson has been in contact with Ships in the Sky, an artist and activist-led social history project in Hull focused on the town’s former Co-operative department store. Following plans for the building’s demolition, the group fought to save a huge 1963 mosaic fronting the building by the artist Alan Boyson, which imbues a sense of history and place on the surrounding high street. After a long battle with stakeholders, the significance of the work has now been acknowledged with a Grade II listing.

Dr Pearson’s research provides important scholarly background and knowledge for campaigns such as these, which aim to ensure the best examples of architecture and public art are recognised and preserved for the future. It also contributes to a broader public understanding of their place in our communities. Often everyday in function, she shows how co-operative buildings were suffused with the social aspirations of the movement. Their legacy extends far beyond their physical presence – and continues even when the co-operative has left the building.