The number of energy co-operatives in Germany has grown from eight to over 800 in a decade – the sector has 160,000 members and now accounts for 10% of all German co-ops. One of the reasons for this growth is the Energiewende, or energy transition, which aims to switch Germany to a renewable energy economy, leaving nuclear and fossil fuel behind. Legislative support for the Energiewende was passed in late 2010.

But nationally there is still a challenge to get renewable energy projects accepted, especially by smaller communities who would potentially receive the most benefit. ‘Please, not in my back yard’ has been a cry heard in response to many renewable energy project proposals, particularly those involving onshore wind farms in rural areas. Dr Andreas Wieg, of the -Deutsche Genossenschafts- und Raiffeisenverband e.V. (DGRV), the federation for German co-operatives, shared experiences of NIMBYism – and how it can be addressed – with delegates at the 2016 Community Energy Conference.

“What we have learnt – the central message we share all over the world for community energy – is why it is important to have community, or citizen, energy projects.” Without community involvement, said Dr Wieg, acceptance of renewable energy is harder. It is the sense of ownership that makes them work.

Around 90% of Germany’s energy co-ops are in solar energy, as not as much money is needed for the initial investment, and the project development – installing solar PV panels compared with wind turbines – is not as risky. Around 150 of the 800 energy co-ops are in district heating systems.

“We have the Energy Transition law,” said Dr Wieg. “We have a feed-in tariff system, and the obligation of the grid operators to buy all the green energy produced by PV or wind energy – so it used to be very easy for everybody, including these energy co-ops, to invest in green energy.”

Under a feed-in tariff (FIT), eligible renewable electricity generators, including homeowners and communities, are paid a cost-based price for the renewable electricity they supply to the grid.

Germany has seen €1.8bn (£1.53bn) of investment in renewable energy, with 1GW of installed capacity. But just as legislative decisions in the UK have impacted community energy, so too have recent decisions by the German government. A survey by DGRV earlier this year showed the number of newly founded energy co-operatives fell by 25% in 2015.

“The challenge for community energy co-operatives in Germany is the drop in the feed-in tariff over the years,” said Dr Wieg. “Now it is not really possible to invest in solar energy projects, so investment in energy co-ops has stopped for two, three years. The main question for us is will we get better FITs in the future or not?”

This is in doubt, given recent reforms to the Germany Renewable Energy Act (EEG). Germany’s share of renewable electricity generation increased from 3.6% in 1990, when the law was enacted, to 30% in 2015. However reform passed this summer means that from 1 January 2017, FITs will be replaced with an auction system for most renewable technologies – market-based incentives for renewables investors, instead of state-determined payments for green power fed into the system.

“For big solar projects, you have to participate in an auction,” said Dr Wieg, “but in the last amendment of the renewable energy sources act the parliament decided to make an exemption for solar energy projects up to 750kW, which is very good for our smaller energy co-ops.” Parliament also decided to adjust the FIT for solar plans.

“The auctions for wind energy are a bad situation for citizen energy projects because you have the risk of project development and now you also have the risk of losing the bid,” he said. “This is a problem – but, surprisingly, maybe because of lobbying work, we got a special rule for citizen energy for wind energy auctions. So hopefully some of these smaller decentralised energy companies will be able to participate. There is hope.”

Dr Wieg added that there was also hope in the form of direct delivery inside houses, bringing new possibilities for housing co-ops, and business opportunities for energy co-ops, through district heating, energy efficiency, mobility and regional development.

Read more from the 2016 Community Energy Fortnight at www.thenews.coop/CEF16

Acceptance by communities is in addition to these problems. So how can this be addressed? “We’re in a business school,” said Dr Wieg. “What would an economist say to solve the NIMBY problem? By creating a financial incentive.”

The minimum share to become a member of energy co-operatives in Germany is €50 (£43). For 90%, members need around €100-200 (£85-170). The average is €652 (£554) due to the higher investment needed in district heating systems. If the co-op pays a dividend, participants get around €200 (£170) back a year.

“If you were getting €200 a year for a wind turbine in your back yard, would you have a problem with that? Possibly not,” said Dr Wieg.

“Some kind of financial return is part of the solution, but of course it’s not the main part.

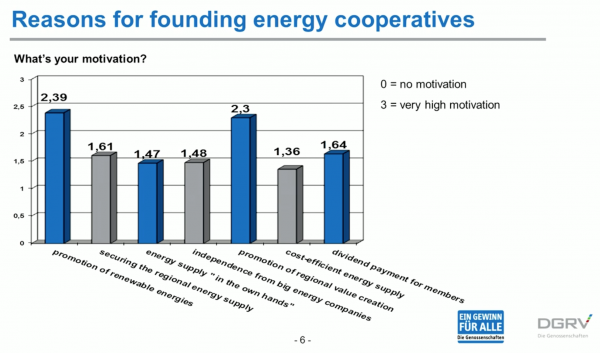

“We asked the board members of these energy co-ops: ‘Why do you put so much of your personal time and your spirit and your talent into an energy co-op?’ They said: ‘There’s an energy transition going on in our country, and we would like to participate in it. We want to promote the energy transition in our home region’.

“On one hand an energy co-operative is about energy, but on the other it is about supporting the local economy, the local community.”

He gave the example of a local football club, which was told it needed a roof on its stands. “The football club didn’t have the money to finance this, so the local energy co-op said ‘OK, we’ll invest and rent the roof top space of this new roof over 20 years. The members, they got a very small financial return, but they were doing something for their community, by investing in their local football club.

He gave the example of a local football club, which was told it needed a roof on its stands. “The football club didn’t have the money to finance this, so the local energy co-op said ‘OK, we’ll invest and rent the roof top space of this new roof over 20 years. The members, they got a very small financial return, but they were doing something for their community, by investing in their local football club.

“The football club members had a discussion. ‘What can we give back to the members of the energy co-op? Maybe a season ticket over 20 years – or a sausage for each game..?

“This is a nice little story, but it shows very well why community energy is important for the energy transition. Because in most of these projects local craftsmen or service companies are involved, they build up and maintain the plans; local banks (including co-operative banks) are involved in these projects, the local authorities get tax… The whole community benefits.”

Another success story is the Energiegenossenschaft Odenwald, a co-operative founded in 2009 to develop and expand renewable energies in the Odenwald region of Hesse while improving energy efficiency and energy saving.

Its central hub is the House of Energy, a former brewery transformed into a space where public administration institutions sit side by side with energy consultants, architects, craftsmen and mortgage lenders willing to answer customer questions relating to energy. The House of Energy also has a canteen, kindergarten, parking lots and public event and exhibition spaces.

The co-operative has seen €17.5m (£14.8m) of investment, and its implementation saw 2,4oo orders tendered to 250 local companies – again ensuring community involvement.

The co-operative has seen €17.5m (£14.8m) of investment, and its implementation saw 2,4oo orders tendered to 250 local companies – again ensuring community involvement.

“It has hosted club nights, classical music concerts, a public viewing of Euro 2016 matches and the 3rd Hessian BBQ contest,” said Dr Wieg.

“A lot of people use this space, it’s revitalising the community – and that’s why energy co-ops, community energy, renewable energy, citizen energy, is so important for the energy transition. You involve the people, and it’s not just a financial investment, you create ownership. People think, ‘that’s mine, that’s my project’.

“Then if you have this kind of ownership, this kind of feeling, you create acceptance for renewable energy.”